2015 update. Our updates on SCN1A mutations and Dravet Syndrome are amongst our most frequently read posts. Therefore, following the tradition of annual reviews that we started last year, we thought that a quick update on SCN1A would be timely again, building on our previous 2014 update. These are the five things about SCN1A that you should know in 2015.

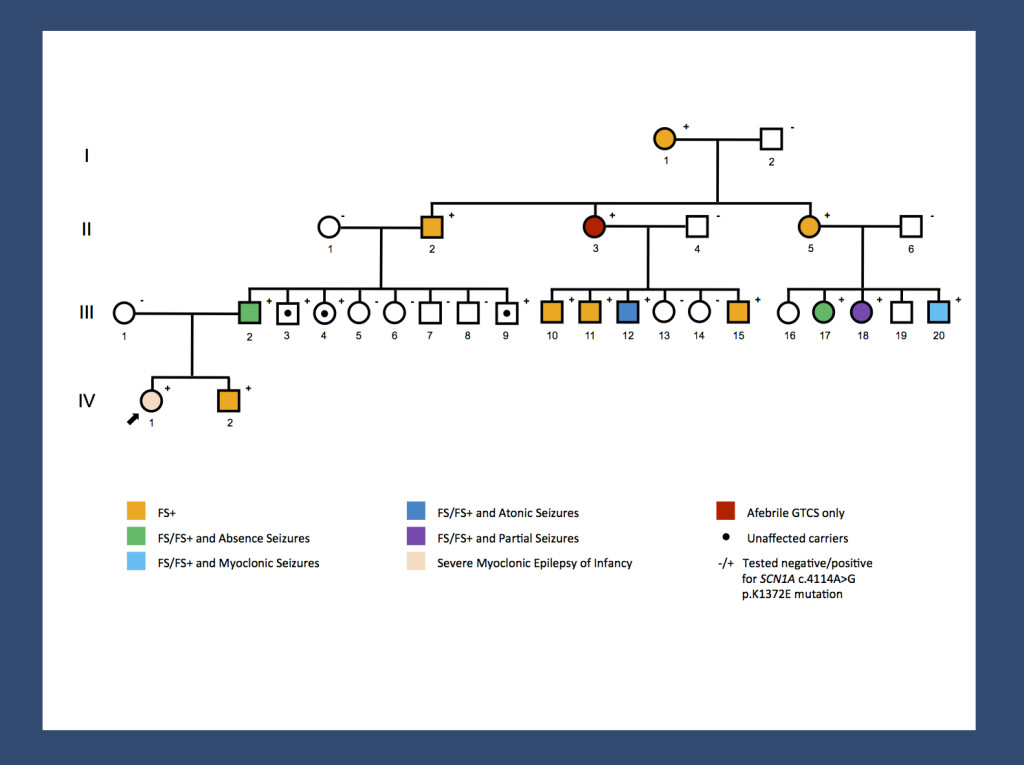

Re-posting one of our figures from November 2013 and May 2014 – a pedigree of a large GEFS+ family with 14 affected and 3 unaffected carriers published by us last year. A missense mutation results in a broad range of phenotypes spanning unaffected carriers, Febrile Seizures Plus (FS+) phenotypes and Dravet Syndrome. The range of phenotypes seen in this family suggests that SCN1A is not the entire story. It will be interesting to investigate whether the modifying factors are genetic or non-genetic. The pattern of phenotypes suggests some intra-familial factors.

1 – SCN1A databases. The SCN1A gene is not only a well-researched, but also a well-documented gene. There are at least two databases in addition to ClinVar and HGMD that review and interpret the reported mutations in the SCN1A gene including the Antwerp SCN1A database and a recently published database that was last updated in February 2015. Accordingly, there is much data out there regarding the mutational spectrum about this gene. It will be interesting to see whether any new patterns will emerge from these large datasets.

2- Population frequency. Thanks to a study in Denmark, we now know about the population frequency of Dravet Syndrome due to mutations in SCN1A, which is 1 in 22,000. To put this into context of more common genetic diseases, the frequency of Trisomy 21 is 1 in 800, the frequency of cystic fibrosis is roughly 1 in 3000, and the frequency of Fragile X Syndrome is 1 in 5,000. The frequency of Dravet Syndrome is comparable to Rett Syndrome (1 in 15,000). While less common than other genetic disorders, it is probably the most common epileptic encephalopathy caused by a single gene.

3 – Febrile Seizures. Finally, SCN1A is not only implicated in severe fever-related epilepsies and rare familial epilepsies, but it has also made an entry as a susceptibility gene for Febrile Seizures, the most common seizure type in children. In a large and well-powered study last year, common variants in SCN1A were found to predispose to Febrile Seizures. Finally, our datasets had sufficient power to identify converging pathways. SCN1A, but also SCN2A seem to be master regulators of excitability of the CNS. They are implicated in various epilepsy phenotypes through various genetic mechanisms ranging from common variants to rare monogenic variants.

4 – Recessive variants. Speaking of genetic mechanisms, with the increasing availability of genetic data, it was virtually inevitable that the role or recessive SCN1A variants would come up at some point. Some publications claim to have identified families and individual patients with recessive inheritance in SCN1A. My word choice already indicates that I feel that these findings require some caution in interpretation. Particularly with recessive variants, it is difficult to tell signal from noise.

5 – Cannabidiol. In 2015, we should mention cannabidiol in the setting of Dravet Syndrome. Cannabidiol (CBD) is one of the active compounds in cannabis and probably the compound with the strongest antiepileptic property. In a 2014 review, Devinksy and collaborators make the case that Dravet Syndrome may be one of first epilepsy syndromes where systematic clinical trials on CBD may be worthwhile undertaking and there are efforts to obtain FDA approval. The mechanism of action of CBD is unclear with multiple potential mechanisms, none of which directly relate to the pathophysiology of Dravet Syndrome. The fact that CBD is currently being investigated in Dravet Syndrome is partially because Dravet Syndrome is one of the most common, well-defined epileptic encephalopathies, which allows for a systematic clinical study. In our previous posts, we highlighted the reason why gene identification is important even though treatment options may appear elusive at the time of discovery. The current efforts with respect to CBD highlight yet another twist – awareness, diagnosis and building a community for clinical trials are intrinsically connected.

Dear Dr. Helbig,

your constantly most valuable and updating blogs on topics of epilepsygenetics are a treasure!

This today blog urges me to comment, that from my view

1. changes in SCN1A gene sequence occur also in healthy subjects (a fact, that creates difficulties in human genetic counseling). Genotype – phenotype corelations are difficult to build up in the “SCN1A-world” and the former belief, that truncating mutations are connected with Dravet-pehnotype, is not a safe knowledge as we have believed some years ago.

2. Dravet-syndrom is not an epileptic encepahlopathy (as many/most in the scene claim). Remember West-syndrome, remember CSWS or Landau-Kleffner-S.: Steroids suppress the epileptic processes and the patient “resurrect”. I do not know any study showing that this can happen in Dravet syndrome: Good treatment is good treatment is good treatment – for sure! But even if treatment difficulties have been overcome and if there is seizure freedom and EEG “cleaning” – the cognitive problems remain.

Best wishes,

Ulrich Stephani