GRIN2A. “Certainty” is a word that can only be used so often in epilepsy genetics—and GRIN2A has demonstrated a somewhat puzzling tension between “certainty” and “uncertainty”. For example, the association between GRIN2A and focal/multifocal epilepsy with/without centrotemporal spikes, as well as risk for ESES, is well understood at this time. Likewise, the relationship between speech disorders—a unique feature in neurodevelopmental disorders—and GRIN2A has been established. However, as our knowledge of GRIN2A has expanded, our understanding of phenotype as it relates to severity has continued to grow uncertain. Even within the same family, GRIN2A may have a wide phenotypic range. And so, one of the mysteries of GRIN2A reveals itself: how can a gene that has such specificity in some of its phenotypic aspects simultaneously have such wide variability?

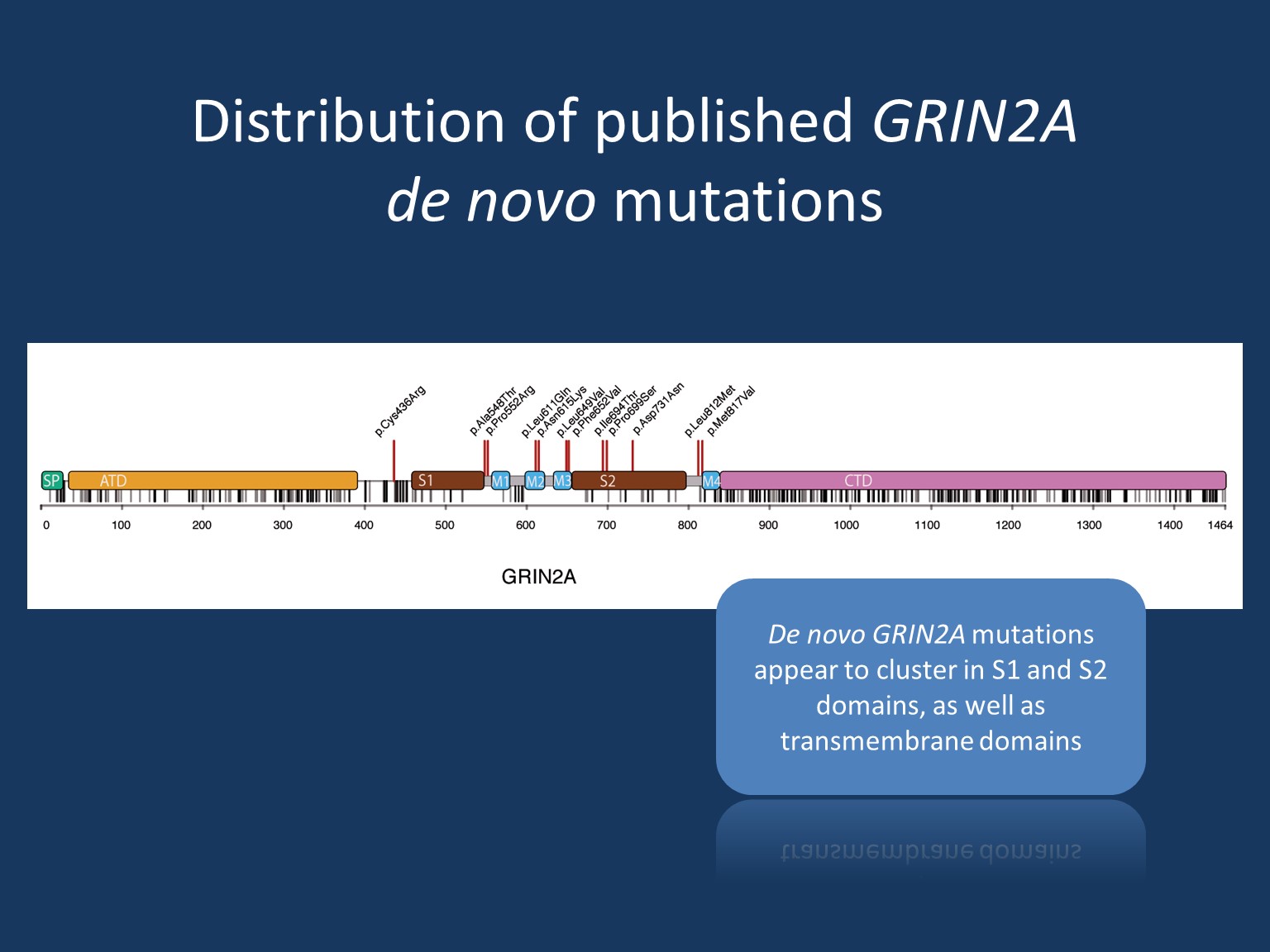

Figure from Strehlow, Heyne, Lemke 2015: Distribution of de novo mutations in comparison to single nucleotide variants according to the ExAC browser – a data base of genetic variants taken from >60.000 healthy individuals (unique – grey, recurrent – black)

Variability. The spectrum of phenotypes associated with genetic alterations in GRIN2A is very broad and ranges from possibly unaffected to severe encephalopathy. At this time, it remains unclear what additional factors might modify phenotypic severity—particularly for family members carrying identical GRIN2A variants. Given that phenotypic variability is most likely associated with haploinsufficiency, one may presume that each carrier is predisposed to a variety of factors that may/may not increase compensatory mechanisms for the associated loss.

Phenotypes. Mild intellectual disability (ID) is a common feature, though there has been a range of severity reported. ID is believed to occur independently of speech and epilepsy. In some families, affected individuals present with a relatively mild phenotype of learning disability and/or mild speech disorders – not necessarily associated with epileptic seizures. Epilepsy in GRIN2A includes spectrums of focal/multifocal epilepsy and epilepsy aphasia. The spectrum of focal epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes comprises classic Rolandic epilepsy (RE), atypical benign partial epilepsy (ABPE), continuous spikes and waves during slow-wave sleep syndrome (CSWS) and Landau-Kleffner syndrome (LKS). The epilepsy aphasia shows phenotypic overlap in particular to CSWS and LKS. Finally, severe epileptic encephalopathy is a rarer but known presentation of GRIN2A, particularly in those with de novo missense variants in the transmembrane or linker domains.

Loss-of-function. Given the phenotypic similarity, it is believed that truncating variants and pathogenic missense variants located in the amino-terminal and ligand-binding domains have a similar mechanism. In turn, pathogenic missense variants in the transmembrane or linker domains may operate differently on a molecular level. It was previously hypothesized that a lack of GluN2A expression due to truncation and haploinsufficiency would subsequently be compensated by an increase of GluN2B expression, however, recent evidence suggests that this compensatory mechanism does not hold true in physiological models. Rather, haploinsufficiency is now the presumed mechanism for truncating variants as well as variants located in the amino-terminal/ligand-binding domains.

Gain-of-function. Considering the stark contrast in phenotype, it is unlikely that pathogenic missense variants in the transmembrane/linker domains have the same mechanism as the aforementioned. Rather, it is likely that these variants have a form of a gain-of-function mechanism. When considering the mechanistic possibilities of gain-of-function, one must consider a resulting dominant-negative effect vs. an effect leading to a unique and abnormal functional outcome. In the case of a dominant-negative effect, one can suspect a loss-of-function >50% but not to the extent of a total loss. Researchers may gain insight into the nature of the gain-of-function effects related to GRIN2A through memantine, a specific NMDA receptor blocker that has been shown to normalize NMDA receptor function in vitro. Application of memantine in a patient with GRIN2A encephalopathy resulted in marked reduction of seizure frequency and other improvements—suggesting the mechanism of pathogenic variation to be related to functional overactivity. However, this observation on a single patient remains to be confirmed in additional cases. Conversely, a carrier of compound heterozygous truncating variants in GRIN2A was reported with severe developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. This report provides unique insight into the phenotype of a total loss. This perhaps suggests that a dominant-negative mechanism remains a possible cause of GRIN2A epileptic encephalopathy.

This is what you need to know. Pathogenic variants in GRIN2A can lead to remarkable phenotypic variability, ranging in severity from apparently unaffected to developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. Epilepsy aphasia, focal/multifocal epilepsy, mild intellectual disability, and speech disorders are common. More recent research has elucidated some genotype-phenotype correlations, particularly in terms of gain of function variants being associated with the most severe phenotypes, but more research is needed to fully explain the phenotype variability seen in GRIN2A-related disorders.