Half Moon Bay. I am on my way back from the Precision Medicine Workshop at Half Moon Bay, realizing again that blog posts from scientific meetings are often boring and difficult to write. However, let me try to put together a few thoughts about this meeting. Basically, there are three challenges for epilepsy genetics in the era of precision medicine.

Disclaimer. Let’s put up the disclaimer first. This is NOT the official summary of the meeting, which will appear as a consensus statement or white paper in the near future. I am simply listing a few impressions that I thought would be worthwhile sharing. As all participants are bound by a confidentiality agreement, I have run this post by the workshop organizers. Here are three challenges that you might want to think about.

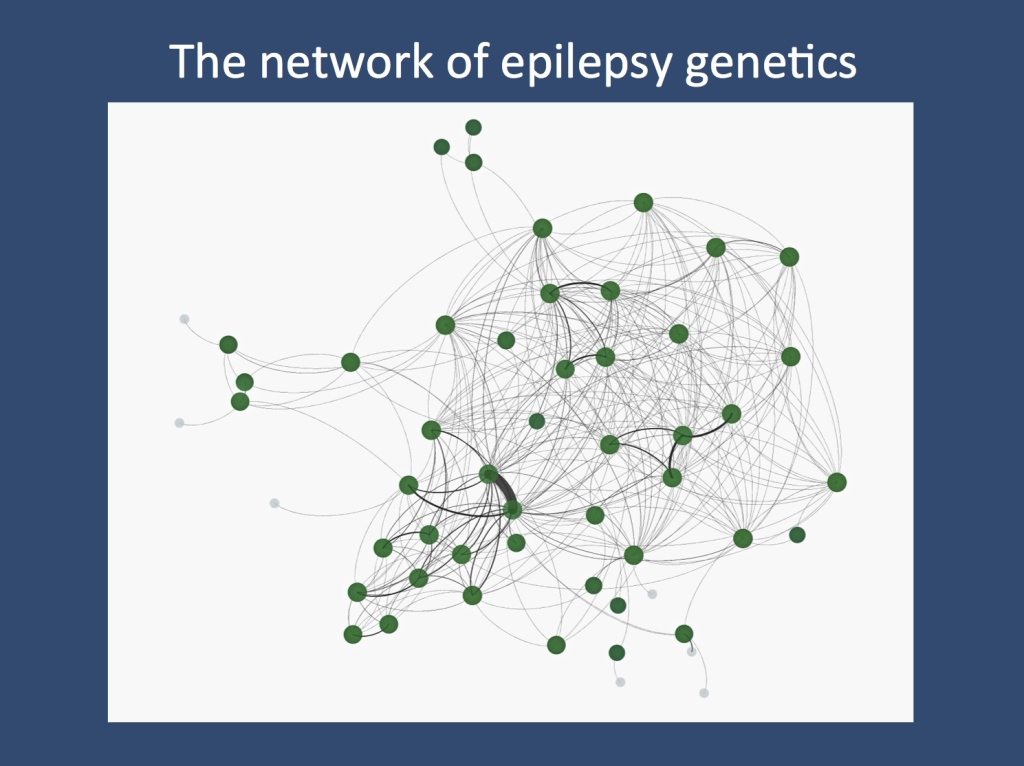

The network of epilepsy genetics. Dan Lowenstein had put together a network of 68 participants of the Half Moon Bay workshop, highlighting joint publications among individuals. The lines represent publications with joint authorships, demonstrating that the epilepsy genetics community is a highly connected and interactive group.

Precision diagnostics. Are we ok with how we make a genetic diagnosis or do we need better tools and standards when it comes to assessing the pathogenicity of variants? Let me give you an example. In many patients with presumable genetic epilepsies we identify genes that were never implicated before. Currently, we do not have a common consensus on what we define as pathogenic, and there has been a lot of interest in trying to find common ground. The community may in fact want to get together and discuss joint standards. Also, we have jointly stuck up our hands up to apply for expert status within the NIH/NHGRI-supported ClinVar/ClinGen initiative. Our basic consensus was: we see great promise in this and if we don’t do it, no one else will.

Model systems. In the current discussion about the fast advances in human genomics, it might sometimes appear that model systems have become less important. Nothing could be further away from the truth – many of the genetic findings in the field require functional validation or assessment. Also, model systems will be crucial for compound screening as demonstrated in the “Dravet fish model” last year. I realized that there are increasing efforts in the community to adapt to the rapid discovery pipeline in gene discovery by providing medium or fast throughput screening systems. I think that there is a convergence of ideas that will slowly, but definitely develop into pipelines connecting gene findings, model systems and compound screening. Quote of the day: “We decided not to use kainic acid anymore”.

Clinical trials. We realized that one important member of the discussion was absent from the meeting – health insurance providers. In many states in the US and many countries worldwide there are ongoing issues regarding reimbursement of genetic tests. The refusal of health insurance providers, pointing out a lack of evidence and the experimental status of high-throughput genomics is reminiscent of the early times of the MRI – another analogy that could be added to our previous blog post about similarities between imaging and genetics. However, rather than viewing insurance companies as the scapegoat, I believe that we have taken a rational and productive view that it might be worthwhile to sit down jointly with health insurance representatives and discuss what needs to be done. Basically, there is little doubt in the epilepsy genetics community that early high throughput sequencing leads to earlier diagnosis and altered management in a relevant subset of patients. Also, the “intangibles” such as the relief for a family having received a diagnosis is very relevant. I believe that the workshop participants including researchers, family advocates, and representatives of the industry have jointly indicated that measuring and documenting the outcomes of genetic testing will be invaluable.

Thank you. There are many people and sponsors to thank who made this workshop possible. I usually pick one or two people for my end-of-post shout-out and I wanted to use this opportunity to thank Dan Lowenstein and Cate Freyer for making this meeting happen.