NBIA. Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) is a group of mainly recessive disorders that present with progressive dystonia and dementia. The common feature of these diseases is the excessive accumulation of iron in the basal ganglia. NBIA is very rare and usually not discussed in the context of epilepsy. However, a recent paper in Brain reviews the phenotypes of beta-propeller associated neurodegeneration (BPAN), a novel X-linked disorder with brain iron accumulation. In childhood, the phenotype shares similarities with atypical Rett syndrome and other epileptic encephalopathies, raising the question to what extent the epilepsies that we investigate may be neurodegenerative disorders.

PKAN, INAD, MPAN, BPAN. In 1922, Hallervorden and Spatz described a familial disease that was characterized by a severe and progressive neurodegenerative disease starting between the age of 7 and 15. Patients were found to have progressive dementia, spasticity, rigidity, dystonia, and choreoathetosis. The disease was later found to be accompanied by excessive deposits of iron in the basal ganglia. These deposits appeared as dark spots on the MRI, which became known as the “eye of the tiger” sign. A mutation in PANK2 coding for pantothenate kinase was found to cause this disease, which was subsequently renamed PKAN – pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration. The name Hallervorden-Spatz disease is no longer preferred, given Hallervorden and Spatz’s complicity in murderous Nazi programs. Over time, other diseases with related imaging findings were identified, including infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy (INAD) due to mutations in PLA2G6 and mitochondrial membrane protein-associated neurodegeneration (MPAN) with mutations in C19orf12. Both disorders are characterized by progressive dementia and movement disorders, but may present earlier than PKAN. In 2012, WDR45 mutations were found to underlie a novel NBIA subtype, which was initially termed static encephalopathy with neurodegeneration in adulthood (SENDA). “Static encephalopathy” referred to the first phase of the disease, which resembled various neurological disorders in children, including epileptic encephalopathies.

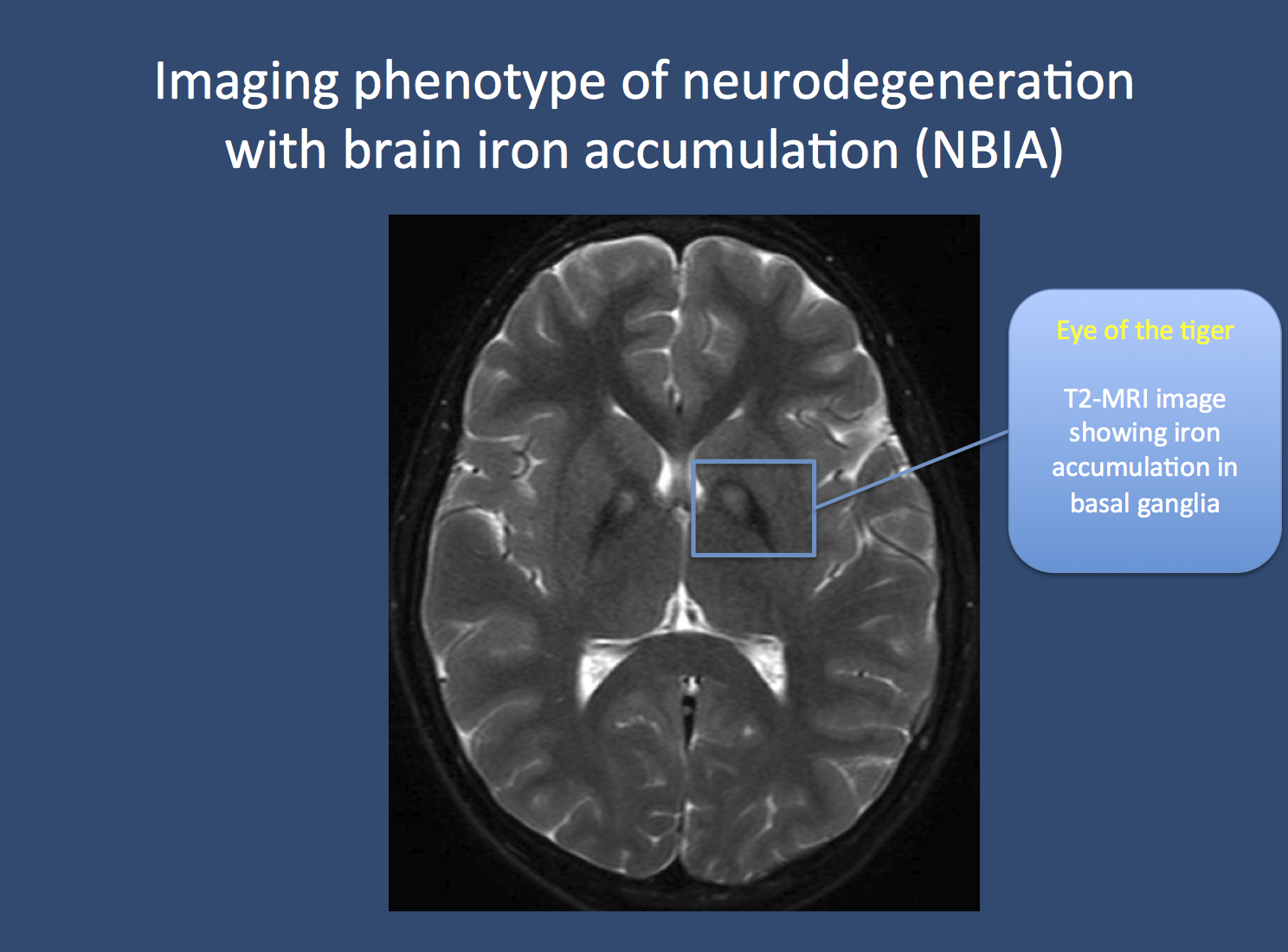

The eye of the tiger. Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN), formerly known as Hallervorden-Spatz disease, is usually associated with a pathognomonic finding on MRI imaging. Due to the accumulation of iron in the basal ganglia, two black spots can be seen, which is referred to as the “eye of the tiger” sign. PKAN is part of a group of disorders referred to as neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Image from Wikimedia commons (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pkan-basal-ganglia-MRI.JPG), within the framework of the Creative Commons license.

From SENDA to BPAN. Hayflick and colleagues reviewed the clinical features of 23 patients with mutations in WDR45 and described the phenotypes in detail. WDR45 is a so-called beta-propeller protein, which is assumed to be involved in autophagy, the breakdown of cellular components through lysosomes. Given the properties of the protein involved, Hayflick and collagues opted to call the phenotypes BPAN, beta-propeller associated neurodegeneration, as “static encephalopathy” did not entirely capture the early presentation of the disease. In the early phase of the disease, patients were found to have global developmental delay, epilepsy and stereotypies, i.e. repetitive movements such as hand flapping. Particularly the latter reminded the authors of other diseases including Rett Syndrome and atypical Rett Syndrome. The epilepsy phenotypes comprised myoclonic, astatic and absence seizures. Furthermore, the authors suggest that neuroimaging might be normal in childhood. In young adulthood, dystonia, parkinsonism and progressive dementia was noted and the MRI showed basal ganglia iron deposits. WDR45 is located on the X-chromosome and all patients had de novo mutations in this gene, turning BPAN into the only dominant form of NBIA.

Neurodegeneration and the epileptic encephalopathies. On several occasions, we have discussed the issue whether some of the epileptic encephalopathies might be masked neurometabolic or neurodegenerative disorders. Usually, patients with new-onset epileptic encephalopathies are screened for a broad range of these conditions and the results are usually negative. This is in line with the negative findings from many large-scale exome studies in neurodevelopmental disorders. Rare exceptions might be some families with recessive inheritance, as in the case of autism. The early phenotype of BPAN was so striking to the authors that they suggest the inclusion of WDR45 in gene panels for epileptic encephalopathies. Large studies using gene panels or exome sequencing will answer the question whether WDR45 is a gene that is repeatedly encountered in epileptic encephalopathies.

Pingback: ST3GAL3 and exome sequencing in autosomal recessive West Syndrome | Beyond the Ion Channel

Pingback: G proteins, GNAO1 mutations and Ohtahara Syndrome | Beyond the Ion Channel

Pingback: Identifying core phenotypes – epilepsy, ID and recurrent microdeletions | Beyond the Ion Channel

Pingback: TBC1D24, DOORS Syndrome, and the unexpected heterogeneity of recessive epilepsies | Beyond the Ion Channel

Pingback: Treatable causes of intellectual disability and epilepsy that you don’t want to miss | Beyond the Ion Channel

Pingback: Microcephaly, WDR62, and how to analyze recessive epilepsy families | Beyond the Ion Channel

Pingback: SLC25A22, migrating seizures and mitochrondial glutamate deficiency | Beyond the Ion Channel