Ceramide. Sphingolipids are a major component of neuronal membranes and help neurons in intracellular signaling and trafficking. Ceramide is one of the basic building blocks of sphingolipids. In a recent publication in Annals of Neurology, mutations in CERS1, coding for ceramide synthetase, are identified in a family with progressive myoclonus epilepsy – and provides an unexpected linked between a group of storage disorders such as Niemann-Pick disease and Tay-Sachs disease and progressive myoclonus epilepsies.

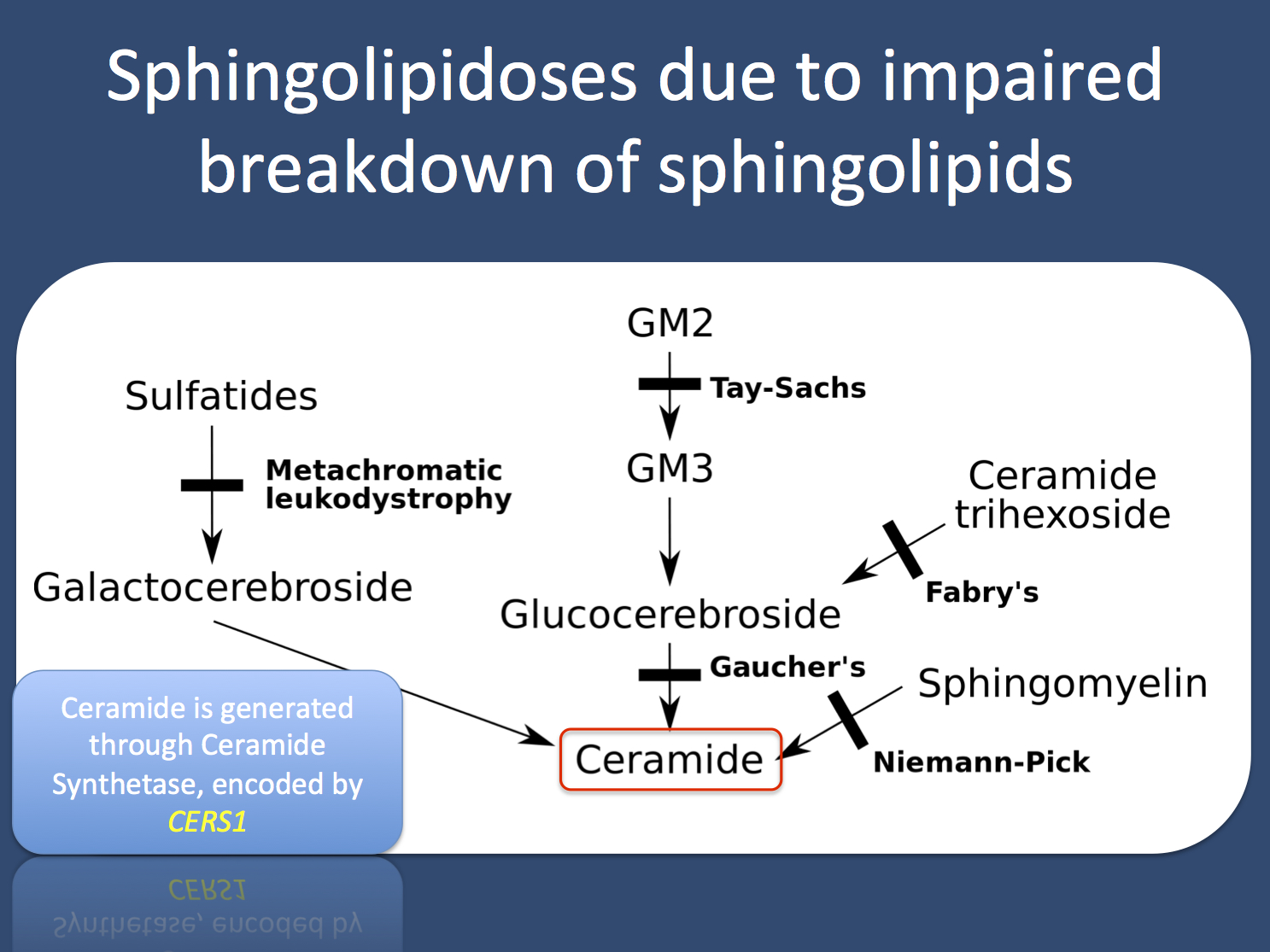

Sphingolipids. When these lipids were identified in the 19th century, they were named after the mysterious sphinx – they basically perplexed researchers because of their properties. Ever since the initial description, sphingolipids have been recognized as important lipids in the cell membrane of neurons. Ceramide is the basic sphingolipid. Once additional residues are added, sphingomyelins, cerebrosides, or gangliosides are produced. Sphingolipids are mainly known through the disorders in which breakdown of sphingolipids is impaired – the sphingolipidoses.

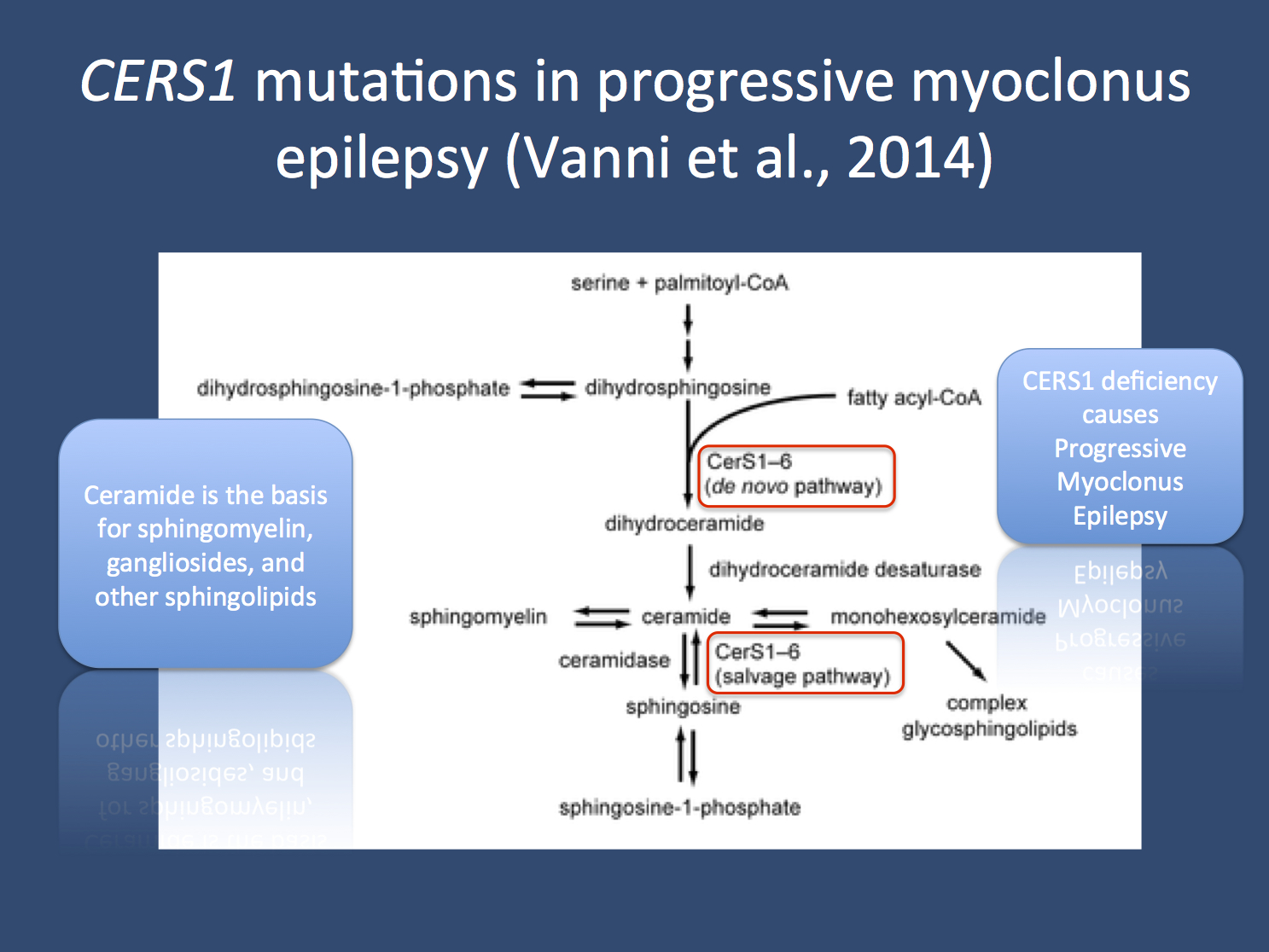

Metabolism of ceramide and sphingolipids. CERS1 is one of the enzymes involved in the synthesis and recycling of ceramide (adapted from Zhao et al., 2011 under a Creative Commons license http://www.plosgenetics.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002063)

Sphingolipidoses. These recessive storage disorders arise from mutations in genes implicated in the breakdown of sphingolipids. This group includes Niemann-Pick disease, Fabry disease, Krabbe disease, Gaucher disease, Tay-Sachs disease, and Metachromatic leukodystrophy. While some of these storage disorders also result in seizures, epilepsy is usually not the main presenting feature in sphingolipidoses. In their recent publication, Vanni and collaborators identify mutations in ceramide synthetase in a family with recessive progressive myoclonus epilepsy – demonstrating that impairment of one of the core enzyme in sphingolipid metabolism leads to a neurodegenerative seizure disorder.

CERS1.Vanni and collaborators investigated the genetic basis in a family with recessive progressive myoclonus epilepsy and four affected individuals. They used a combination of homozygosity mapping and targeted resequencing to analyze possible mutations in a region on chromosome 19, which contained 104 coding genes. After filtering, the variant in CERS1 stood out. When testing the effect of the mutation on the ceramide synthetase genes, they observed a reduced production of ceramide and upregulation of stress markers in the endoplasmatic reticulum. This stress response might lead to apoptosis and possibly represents the molecular correlate of the neurodegeneration seen in the affected individuals.

An overview of the defects in various sphingolipidoses. This group of disorders is due to defects in the breakdown of sphingolipids, which include sphingomyelin, cerebrosides and gangliosides (adapted under a Creative Commons license from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Inborn_errors_of_metabolism.svg)

Animal model. Flincher and toppler are two mouse lines with mutations in the CERS1 gene. These animals also show a phenotype of neurodegeneration and seizures, a convincing parallel to the phenotype of the PME family described by Vanni and collaborators. Furthermore, an accumulation of lipofuscin can be seen in the brains of these two mouse lines. This feature is usually observed in the Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinoses (NCL), a group of mainly recessive neurodegenerative disorders that have progressive myoclonus epilepsies as a presenting feature. While the accumulation of lipofuscin was not seen in biopsies of patients with CERS1 mutations, this highlights a common pathophysiological pathway due to impairment in ceramide metabolism. The findings of the animal study also raise the question how an impaired synthesis may result in an accumulation of subsequent products. In fact, CERS1 is not only involved in de novo synthesis but also recycling of ceramide metabolites, which may be the explanation for this.

Lessons learned. The metabolism of ceramides, sphingomyelins, cerebrosides, and gangliosides is complex. However, these molecules appear to be important components of the neuronal plasma membrane, and defects in their metabolism result in various neurodegenerative disorders. Therefore, enzymes in these pathways are key candidates for yet unsolved cases of progressive myoclonus epilepsies.