How do you feel as a Nobel laureate? For the few of us who aspire to be Nobel laureates one day, there is news for you. You already won it. The Nobel Peace Prize to the EU might not have been the award and format that you were initially thinking about, but despite all the hardships and difficulties that the life of a scientist puts you through, it is difficult to dismiss that the Europe we are working in right now is much different from the continent that our parents and grandparents knew. This became clear to me on my recent trip to Strasbourg.

Some impressions of pre-EU Europe. When I was a kid, we once travelled to France. We left in the middle of the night by car and I fell asleep on the way. I woke up when we were passing the French border. We had to wait quite some time to cross and guards with guns were patrolling the border. As a kid, it felt a bit scared as these guys don’t really smile. Yesterday, taking full advantage of the Schengen agreement, I flew into Strasbourg without any passport controls. It’s the EU’s new secret weapon, as European Council President Herman Van Rompuy put it on Monday, “an unrivalled way of binding our interests so tightly that war becomes impossible.” Two more holiday stories from my childhood. One time, we went hiking in the Bavarian mountains. One trail led us to the Czechoslovakian border. Since the border was on a mountain top, it was only delineated by simple fence posts with signs on them but without any real barriers (the no-go zone was down in the valley). I took a brief step on the Czechoslovakian side. I felt so bold for having entered the communist Eastern bloc for a little more than a second, which was a big no-no back then. Also, we often travelled to the Harz mountains, a mountain range in the middle of Germany that is probably best known for its highest mountain, the Brocken or Blocksberg. The Brocken was in the former East and at night, you could see the blinking red lights that made this mountain even more mysterious than it already was because of all the witch stories. While I am blending European integration, the fall of the Eastern block and German reunification, these are basically different aspects of the same story, the continuing integration of Europe. This became clear to me on my recent trip to Strasbourg, one of the EU’s “capitasl” and the seat of the European Science Foundation (ESF).

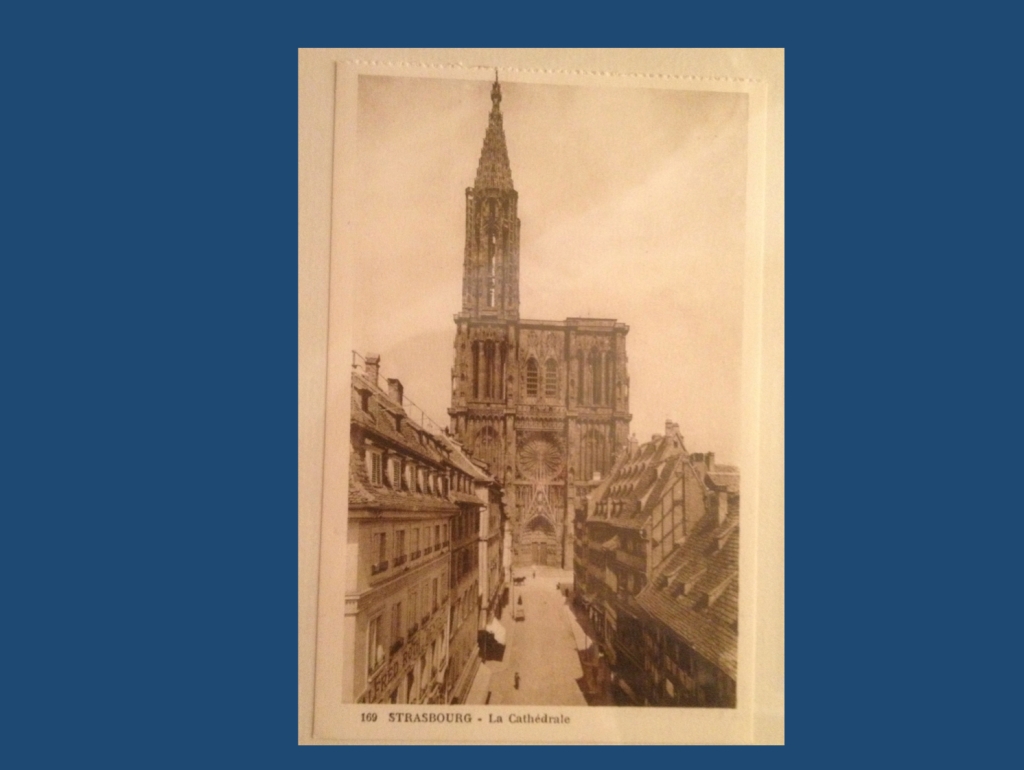

The Strasbourg Cathedral was the highest building of the world between 1647 and 1874. It is a good example of European project management. Aims: “Build a cathedral with two towers”. Deliverables: “Working cathedral in 1647 with two towers”. Risk analysis (usually not a prominent part in EU grants): “We might not have sufficient funding to complete the second tower. In this case, we will exhibit the cathedral as a local attraction.” If you can’t fix it, feature it.

ESF vs. EU grants. EuroEPINOMICS is a so-called Eurocores program of ESF. Within these programs, the participating national funding agencies commit to funding a project from the participating countries. This is a different funding mechanism than centralised EU grants. Due to restructuring of the ESF, EuroEPINOMICS will be the last Eurocores project of the ESF and the entire program will run out in 2014 with the completion of EuroEPINOMICS. Much of the large-scale research in the field currently works on the level of central EU grants. For example, EPICURE was funded through the 6th framework program (FP6), EpiPGX is funded through the 7th framework program and there is currently a new call out in FP7 that includes epilepsy called FP7-HEALTH-2013-INNOVATION-1. The next program will be Horizon 2020 and people are already trying to get a feel for how this framework program might affect the field of epilepsy genetics. Many of our large-scale papers in the last few years including the papers on microdeletions and GWAS in IGE are pan-European productions, nicely demonstrating how tightly we have grown together. In fact, large-scale genetic research as required for modern epilepsy genetics is no longer possible on a national level in Europe and would have required transnational collaboration anyway. Having funding available at a central level has allowed us to perform these studies, which probably would have been difficult otherwise in Europe.

Goodbye Eurocores. Even though the funding mechanism of Eurocores grants seems to be outdated in the face of the large calls for FP6, FP7 and -hopefully- Horizon 2020, there are some very positive aspects about this. I like to tell the story that the first SCN1A-negative Dravet trio we sent for exome sequencing was not from Antwerp, Paris or Kiel, but from Romania, including state-of-the-art IRB and sample quality. By providing incentive to include novel partners, the EuroEPINOMICS project has allowed us to reach out to partners who have not been active in field before and to create a vibrant network of scientists and clinicians working on epilepsy genetics. I always felt that many central EU grants including the central FP6/FP7 grants, ERA-NET and E-RARE grants do not provide this incentive, favouring excellence at the price of integration. Not to mention the hypercompetitive European Research Council grants (ERC), which have excellence written all over them. Having just completed a tiring round of grant reviews geared towards identifying excellent researchers myself, there is a lingering feeling that some parts might go missing in such an environment. In particular, this might be the case for outreach activities such as this blog, giving less “excellent” partners the benefit of the doubt or research diversity. There is an ongoing debate whether the competitive grant application frameworks as seen at the NIH favour conformity rather than diversity.

Open borders. There might be debate about where European research is headed and this might particularly be true for the analysis of complex genetic disorders including epileptic encephalopathies and IGE/GGE. However, there is no debate at all whether such a research will take advantage of an increasingly connected European scientific community. Yesterday, in Strasbourg, one of my colleagues from the States asked me whether it would feel strange to me as a German to visit the Alsace, a region around Strassbourg that has been an apple of discord between Germany and France for centuries and where many places carry German-sounding names. I told her that this hasn’t really crossed my mind and that I simply take this for granted. The bilingual Alsace taxi driver who took me to the airport told me that he usually likes to go shopping in Kehl, Strasbourg’s little German twin city and that many Germans now like to live in the Alsace as the prices are good. In fact, there are few places in Europe where European integration is so self-evident as in the Alsace, up to the point that you don’t really talk about this anymore. And this alone is worth a Nobel Prize.