The need for re-contact. Genotype-driven research recruitment refers to the inclusion of research participants in future genetic studies based on the findings from previous studies. For example, deep sequencing efforts within the EuroEPINOMICS Consortium may generate potentially interesting novel variants that warrant further investigation. In some cases, it might be necessary to obtain more phenotypic information, in other cases, segregation in the family might be of interest. Since many variants are rare in the general population, genotype-driven approaches are particularly attractive, i.e. research participants are selected based on genetic findings. This so-called “bottom up” approach allows for targeted studies without the time-consuming and expensive step of re-screening large patient cohorts. In the future, genotype-driven research efforts will likely become increasingly common, since it is unlikely that large-scale genomic studies alone will be able to sufficiently characterize rare genetic variants. However, approaching patients based on genetic research data raises important questions. Continue reading

Tag Archives: epilepsy genetics

Exome study in IGE questions channelopathy concept

IGE and the hunt for rare variants. Idiopathic Generalized Epilepsy (IGE) or Genetic Generalized Epilepsy (GGE) is one of the most common epilepsy subtypes. Family studies and twin studies suggest that genetic factors play an important role. Some families with mutations in GABRG2, GABRA1 and EFHC1 are known, and recurrent microdeletions are found in 3% of sporadic patients. For the majority of patients, the genetic basis remains unknown, but a heterogeneous pattern of rare variants is expected. Much effort is currently spent on genetic studies in IGE including the EuroEPINOMICS CoGIE study. A recent paper now reports the first exome sequencing in IGE to identify rare variants…

ATP1A3 links alternating hemiplegia of childhood with genetic dystonia and parkinsonism

Alternating Hemiplegia of Childhood (AHC). Acute hemiplegia in children, i.e. weakness of one side of the body, is always a medical emergency. Causes for a sudden hemiplegia can include intracranial bleeds, tumors and rare metabolic disorders. Immediate diagnostic work-up is paramount. In some children, no cause can be found on brain imaging and extensive testing, and the episode remits after hours or days. Strangely, during a following episode, the other side of the body is affected. This condition has been named Alternating Hemiplegia of Childhood (AHC) by Verret and Steele in 1971. AHC is an enigmatic disorder, which is sometimes associated with epilepsy, developmental delay and dystonia. Even though some cases with mutations in SCN1A, CACNA1A, and ATP1A2 have reported, most cases of AHC are unresolved. Given some resemblance with epilepsy and familial hemiplegic migraine, many children with AHC are followed up by epileptologists. The major cause of AHC has now been identified in a recent study… Continue reading

FAME – when phenotypes cross over but chromosomes don’t

Crompton and colleagues recently published the clinical and genetic description of a large family with Familial Adult Myoclonic Epilepsy (FAME). This phenotype is particularly interesting since it provides some insight into how neurologists conceptualize twitches and jerks. It is also a good example that large families do not necessarily result in a narrow linkage region, particularly when centromeric regions are involved.

What is myoclonus? Despite usually mentioned in the context of epilepsy, most people are inherently familiar with myoclonus. Most of us “twitch” when we fall asleep and sometimes experience this twitch as part of a dream. These episodes are entirely normal and are called hypnic jerks, but they give people a good idea of what a sudden, brief, shocklike, involuntary movement caused by muscular contraction or inhibition would feel like. Myoclonus in the setting of epilepsy is usually mentioned as part of a Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy (JME) or Progressive Myoclonus Epilepsy (PME). Please note that both epilepsies use different endings to describe the twitch (“-us” vs. “–ic”). This is mainly convention. Basically, myoclonus is a brief shock-like twitch, which can affect almost every part of the body and can be due to dysfunctions in various regions in the Central Nervous System.

The neuroanatomy of twitching. A motor command from the cerebral cortex has to pass through several steps prior to execution. For example, the simple command of tapping a finger on the table surface is prepared by the cortex through several loops before being sent down your spine. Accordingly, myoclonus can arise from different parts in the brain. (1) The cortical myoclonus is due to a purely cortical source and can be seen in many forms of symptomatic myoclonus. (2) The cortico-subcortical myoclonus is due to feedback from the cortex to other brain areas. This is the myoclonus we see in patients with JME. Both variants may be seen on EEG since the cortex is involved. (3) The subcortical-supraspinal myoclonus is generated in the brain stem or below and is responsible for phenomena such as hyperekplexia or startle disease. Some forms of hyperekplexia, literally “exaggerated surprise”, are due to mutations in genes involved in glycinergic transmission and can be found in some isolated communities such as the Jumping Frenchmen of Maine. (4) Finally, there is also spinal and peripheral myoclonus.

FAME – epilepsy or movement disorder? Familial Adult Myoclonic Epilepsy (FAME) is an enigmatic familial disorder with the triad of myoclonus, tremor and seizures. Several families have been described and two loci on 8q23.3-8q24.11 and 2p11.1-q212.2 for FAME have been established. The underlying genes are still unknown. Crompton and colleagues no describe a large six-generation family with FAME in Australia/New Zealand. The familial disease usually starts with tremor in early adulthood in the affected family members, even though a wide range of age of onset is observed. Interestingly, only a quarter of all affected family members had seizures, which is in contrast to previous studies. Therefore, FAME may actually be better characterized as a movement disorder with concomitant seizures rather than a familial epilepsy syndrome. The authors also point out the difficulties distinguishing FAME from the much more common essential tremor (ET). In particular, the well-described response to β-blockers seen in patients with ET can also be observed in some family members.

Figure 1. The candidate gene landscape of the chr2 FAME region. All genes were searched for the number of hits in PubMed for the listed search terms in an automated fashion. As usual in large linkage intervals, only few genes are known in the context of neurological disorders, while most genes are unknown.

The genetics of FAME. Crossovers during meiosis usually lead to a progressive narrowing of the linkage interval in familial disorders. However, the lack of crossover events leads to very large linkage intervals even in very extended families. The family described by Crompton et al. links to the pericentromeric region of chromosome 2. Pericentromeric regions usually have a low frequency of crossover events, and this phenomenon has also delayed the identification of other familial epilepsies such as Benign Familial Infantile Seizures with mutations in PRRT2. The linkage region contains almost 100 genes and Figure 1 shows the “candidate gene landscape” in this region. While some genes clearly classify as top candidate genes, the majority of the genes in this region are unknown in the context of epilepsy. Therefore, identification of the FAME gene will be exciting and provide us with novel insight on how genetic alterations may produce combined neurological phenotypes.

Be literate when the exome goes clinical

Exomes on Twitter. Two different trains of thoughts eventually prompted me to write this post. First, a report of a father identifying the mutation responsible for his son’s disease pretty much dominated the exome-related twittersphere. In Hunting down my son’s killer, Matt Might describes his family’s journey that finally led to the identification of the gene coding for N-Glycanase 1 as the cause of his son’s disease, West Syndrome with associated features such as liver problems. The exome sequencing that finally led to the discovery was part of a larger program on identifying the genetic basis of unknown, putatively genetic disorders reported in a paper by Anna Need and colleagues, which is available through open access. This paper is an interesting proof-of-principle study that exome sequencing is ready for prime time. Need and colleagues suggest exome sequencing can find causal mutations in up to 50% of patients. By the way, a gene also that turned up again was SCN2A in a patient with severe intellectual disability, developmental delay, infantile spasms, hypotonia and minor dysmorphisms. This represents a novel SCN2A-related phenotype, expanding the spectrum to severe epileptic encephalopathies.

The exome consult. My second experience last week was my first “exome consult”. A colleague asked me to look at a gene list of a patient to see whether any of the genes identified (there were 300+ genes) might be related to the patient’s epilepsy phenotype. Since I wasn’t sure how to best handle this, I tried to run an automated PubMed search for combination of 20 search terms with a small R script I wrote. Nothing really convincing came up except the realisation that this will be an issue that we will be increasingly faced in the future: working our way through exome dataset after the first “flush” of data analysis did not reveal convincing results. Two terms that came to my mind were bioinformatic literacy as something that we need to improve and Program or be Programmed, a book by Douglas Rushkoff on the “Ten commands of the Digital Age”. In his book, he basically points out that in the future, understanding rather than simply using IT will be crucial.

The cost of interpretation is rising. The Genome Center in Nijmegen suggests on their homepage that by the year 2020, whole-genome sequencing will be a standard tool in medical research. What this webpage does not say is that by 2020, 95% of the effort will not go into the technical aspects of data generation, but into data interpretation. For biotechnology, interpretation will be the largest marketing sector.

By 2020, probably more than 10 million genomes will have been sequenced. Data interpretation rather than data generation will represent the most pressing issue.

So, what about epilepsy? “50% of cases to be identified” sounds good for any grant proposal that I would write, but this might be a clear overestimate. Need and colleagues used a highly selected patient population and even in the variants they identified, causality is sometimes difficult to assess. We are maybe much further away from clinical exome sequencing in the epilepsies than we would like to admit. The only reference point we have for seizure disorders to date is large datasets for patients with autism and intellectual disability. While some genes with overlapping phenotypes can be identified, we would virtually be drowning in exome data without being capable of making sense of this.

10,000 exomes now. I would like to predict that after having identified some low-hanging fruits with monogenic disorders, 10,000 or more “epilepsy exomes” would have to be collected before making significant progress. It is, therefore, crucial not to be tempted by wishful thinking that particular epilepsy subtypes necessarily have to be monogenic, as in the case of epileptic encephalopathies or other severe epilepsies. Much of the genetic architecture of the epilepsies might be more complex than anticipated, requiring larger cohorts and unanticipated perseverance.

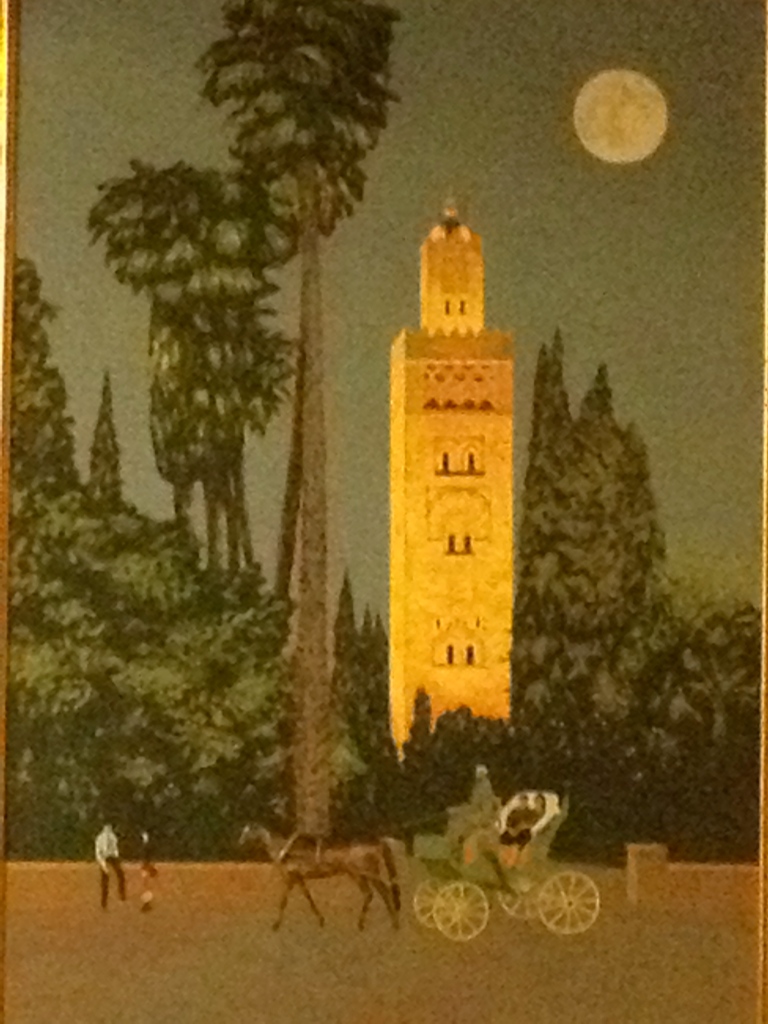

The Marrakesh diaries – DNA colonialism

A 21st century gold rush. Collections of biosamples, referred to as biobanks, are sometimes referred to as the ‘gold of the 21st century‘, as these collections will provide the key for translating the findings of biomedical research into patient treatments. The upcoming revolution of personalized health can only happen if well-curated patient samples for DNA, tissues and other biomaterials are available. In many European countries, large government-funded initiatives are on the way to build these collections. So far, so good.

DNA colonialism. But what does this have to do with colonialism? The phrase of DNA colonialism has a dual origin and was pretty much invented in parallel in a discussion I had with researches in Israel and Morocco. Given that this idea came up twice independently within a few weeks, it prompted me to put this together as a blog entry. DNA colonialism refers to the phenomenon that researchers from “developed” countries obtain valuable biosamples in “developing” countries for their research. Collaborations with emerging countries are becoming increasingly important given the particular genetic architecture in these countries, which lends itself to gene discovery. Often collaborating researchers in the emerging country are only involved on a very basic level and are sometimes not even involved in the final publication of the data. This phenomenon is frequently observed in the literature when the author list of novel gene findings in consanguineous families do not include researchers from the respective emerging country.

DNA mining leaves little behind other than empty mines. Within these bilateral collaborations, the genetic architecture of the “developing” countries is mined by Western researchers, which is sometimes interpreted as a modern form of colonialism. While there is little doubt that the findings originating from this research are important, there is little benefit for the emerging country. Examples where the gene findings in families are translated into screening programs are rare and -to my knowlegde- only exists for Bedouin population in the Southern part of Israel. Treatment options based on these findings are even rarer. Instances, in which a partnership between a “developing” and “developed” country has resulted in the creation of infrastructure on site are few.

New rules for “DNA trading”. What has to be done to avoid DNA colonialism and what would constitute a fair trade agreement to enable a productive partnership rather than an exploitation of the genetic architecture? Naturally, there is not a single definite solution for this issue, but at least two points may be raised in this context.

Biosamples are becoming more valuable. First, the relative value of biosamples in relation to genetic technologies is increasing. The price for Next Generation Sequencing technologies is constantly dropping and samples can be analyzed at much lower costs. This will naturally help the relationship between both partners as the effort to obtain sample is increasingly valued. Also, there is an increasing awareness regarding the IRB-related issues surrounding biosamples. While many researchers still feel that they lose the control over a given biosample once the sample leaves the country, the entire field is getting increasingly sensitized to these issues. Modern material transfer agreements might include well laid-out plans for what happens with samples once they cross international borders.

Redistribution, fostering intrinsic motivation. Secondly, research environments in developing countries would need to provide a commitment towards generating a sustainable infrastructure in emerging countries. Despite the naive impression that building good research environments is not possible in countries outside the Western sphere, there are examples that suggest otherwise. For example, the Kanaan lab in Bethlehem, Palestine, represents one of the of the premier labs worldwide for the research of genetic hearing loss and Dr. Kanaan has a strong commitment to establishing methods and technologies on site. As in many other instances, lack for funding for R&D is not a matter of resources, but of distribution. The question of to what extent pure external incentives such as large amounts of funding might help resolve these issues is uncertain, and one of the key challenges would be to foster intrinsic motivation for these issues in young researchers.

Implementing some of these issues might help researchers in emerging countries establish long-term plans to generate on-site know-how and infrastructure in order to fully participate as equal partners in international research networks. Eventually, the hunt for epilepsy genes does only start with the identification of these variants. If we ever have the hope that genetic findings in the epilepsies will impact on patient care and treatment, we as the EuroEPINOMICS consortium should strongly motivate our collaborative partners in emerging countries to be more than mere sample providers.

The surprising truth of your motivation for epilepsy genetics

Why are we doing what we are doing? Academic research appears to be a rat race of high-strung egomaniacs fighting for grant money, impact factors and ultimately their scientific legacy. In this constant struggle you either make it or you don’t, you publish or perish, depending on how good you can elbow your way through. And finally, make no mistake, it’s all about the money. Unfortunately, many young researchers are given this dire, coldhearted perspective by senior scientists and supervisors. Your PhD either results in a Nature or Science paper or you’re gone. Family? Not my problem. Holidays? Why are you even asking. This blog post is about the hidden secrets of human motivation, trying to point out some basic fallacies in these arguments. My brief answer to this is: “This is so 1995…”

Party like it’s 1995. Just imagine we are back in 1995 and we were asked the following question. “I would like you to tell me our opinion about the possible success of two different online encyclopedias. Type A is financed by the world’s largest software company, which has dedicated a generous budget to this project that pays both a highly qualified staff of writers and an experienced management team. Type B is a voluntary encyclopedia with no budget, established through people dedicating their spare time. In 15 years from now, which online encyclopedia will still exist?” In 1995, there was probably not a single person who would have put his or her money on Encyclopedia B based on this description. However, Encyclopedia B has evolved into one of the world’s largest online knowledge repositories, while Encyclopedia A closed its doors for good in 2009.

Wikipedia vs. Encarta. If I tell you that Encyclopedia B is Wikipedia and Encyclopedia A is Microsoft’s Encarta, this story makes sense to you. Daniel Pink provides this example in his book “Drive”, which tries to explain the secrets of human motivation. In brief, in contrast to the prevalent belief that strong incentives such as money or titles are the main drivers of human motivation, this “carrot and stick” method only gets you so far and will produce people being productive for the reward, and not for the issue itself. Pink identifies three elements that are the main drivers of motivation, namely Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose. In brief, Wikipedia became what is today by enabling people to work autonomously, to engage their expertise and to feel a sense of purpose through a shared experience and feedback, something that millions of dollars by Microsoft could not buy.

Motivational theory. Pink’s arguments are nothing new. They are based on scientific investigations by Deci and Ryan in the 1970s, who conducted sophisticated psychological experiments to analyse human motivation and who identified these three elements as part of their self-determination theory of motivation.

Application to research. Uri Alon from the Weizman Institute has re-interpreted these results for the field of science in a freely available comment in Molecular Cell, identifying Competence, Autonomy and Social connectedness as the three elements that apply to science. Competence basically relates to working in an environment that is neither too boring nor too challenging. In research, we are mainly faced with leaving people with a task that is too challenging for their current knowledge level. For example, suggesting that a Young Researcher design a sophisticated genome-wide association study on pediatric pharmacology without any prior knowledge of biostatistics is too challenging, eventually decreasing motivation. Altering the project to a candidate gene screening will eventually increase the researcher’s motivation, despite the possible lack of scientific ingenuity. However, in the end, the second option will be more productive for the team as the young investigator is capable of working at her or his level of competence. Autonomy refers to a related issue. You can only be motivated in science when you perceive a sense of independence and an intermediate level of structure. Not too structured and not too independent. The third strand of motivation in science is Social Connectedness. It’s the proverbial water cooler discussion, the environment that gives you a sense of belonging, the interesting paper that was pointed out by that guy next in the lab next door, the senior postdoc who has nothing to do with your project, but who is happy to have a look at why your PCR isn’t working. Networks have been the main driver of scientific innovations over the past centuries, which is “Where good ideas come from”, as authors Steven Johnson puts it. Naturally, the science network arising from research consortia such as EPICURE or EuroEPINOMICS is much more than just a collection of scientists. These networks are organic entities and the ideal breeding ground for scientific innovation in the field.

The hidden secrets of motivation. How motivation works in science and how to choose projects that are ideally suited for you in epilepsy genetics.

When scientific projects are really well suited for you. Uri Alon goes on to re-interpret these three elements in the context of scientific projects, suggesting a so-called TOP model (Figure). Projects are particularly well suited for you if they manage to completely engage you, drawing on your talents, your passions and your goals. Epilepsy genetics of the future will be multifaceted with many different niches and subfields that might allow a broad range of scientists with different backgrounds and motivations to contribute. Touching upon diverse fields such as genetics, neuroscience, social sciences, public health, etc., researchers with “cross-over skill sets” will be crucial. The age of the lonely genius researcher hiding out in his secret lab to eventually emerge with a Nobel-prize winning flash of inspiration is over, if it has ever existed. The science of the future will be network science and “chance favors the connected mind”.