Perspective. This blog post is about a topic that I had planned to write about for a while – the intersection of neurogenetics and self-advocacy. This is a potentially loaded topic in many disease areas, and I had held off on writing this for a while. However, when I put together my prior blog post on the different perspectives on stuttering, it occurred to me that I could use stuttering genetics as a vehicle to get these thoughts across. Stuttering genetics is relatively underdeveloped, and I feel that I can speak to the intersection of self-advocacy and genetic research as pediatric neurologist involved in neurogenetics research and as a person who stutters. However, this post is not only about stuttering, it is about how neurogenetics and self-advocacy may be synergistic, adding nuance to both perspectives.

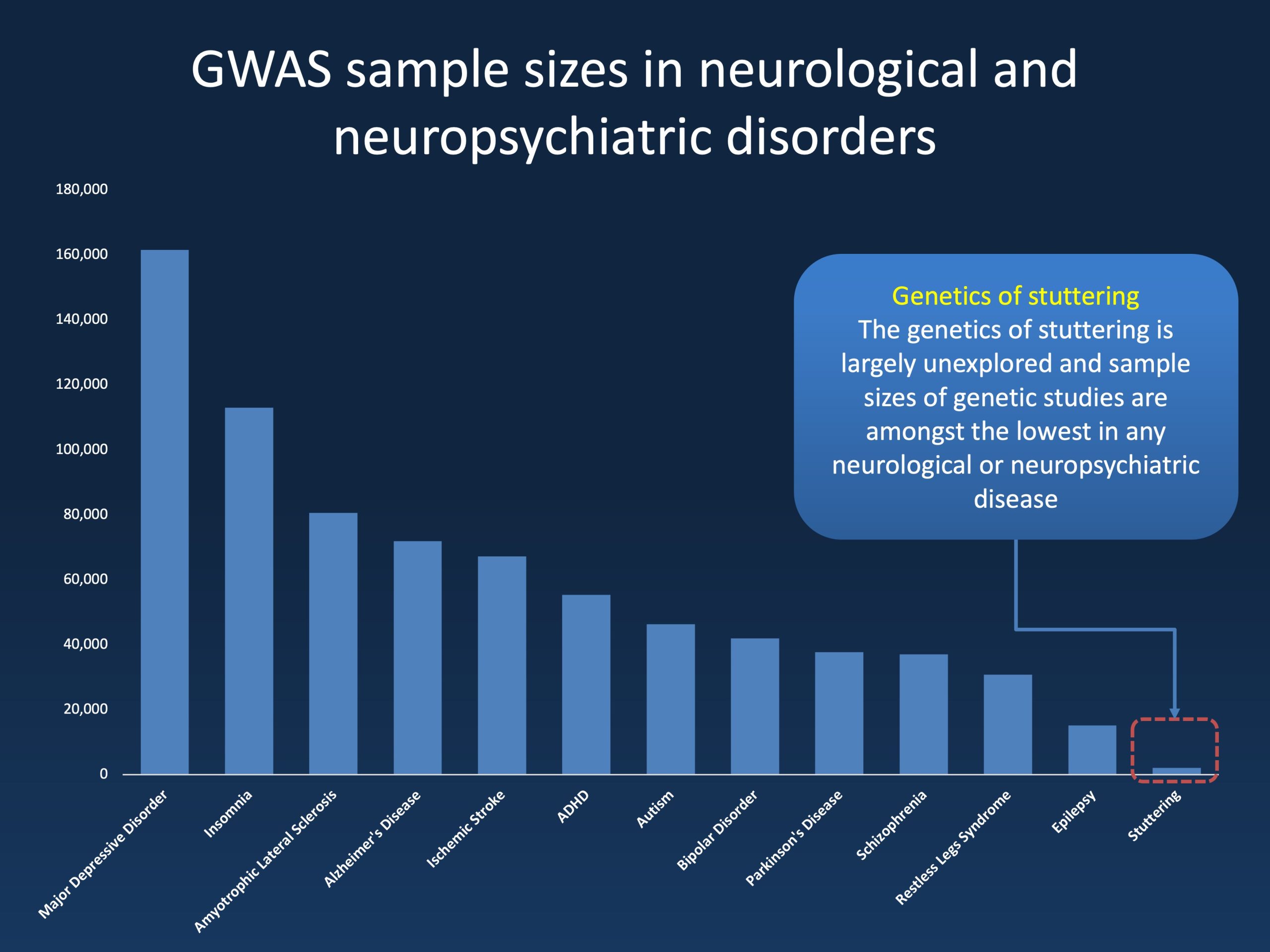

Figure 1. Sample sizes for genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in neurological, neuropsychiatric, and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Stuttering genetics in 2023. Given that stuttering affects 1% of the world population and has a strong genetic contribution, the overall efforts in stuttering genetics are surprisingly subdued (Figure 1). Please don’t get me wrong, this is not any researcher’s fault, but a systemic issue. In fact, many of the research groups performing genetic research in stuttering are the unsung heroes in the field, pushing ahead with an often unappreciated research agenda against all odds. This relative lack of activity and the emerging field of self-advocacy have created an interesting area of discussion – to which degree do we actually want stuttering research to happen, or should we not pursue these issues, leaving questions unanswered that might potentially lead to discrimination and add to stigma?

View from above. Taking one step back, being able to raise these issues is somewhat unique to the stuttering field, as large-scale genetic studies have already been performed in many other neurodevelopmental conditions. The current vacuum creates an almost experimental condition to observe how scientific studies and self-advocacy may interact in many other conditions, highlighting aspects that would otherwise be lost. Here is what the stuttering genetics actually adds to the discussion in neurogenetics more broadly.

Questions about the scientific approach. In a 2022 commentary, Prabhat and collaborators pointed out that scientific publications in the field often include ableist language by referring to lack and deficits rather than differences. This is an issue in neurogenetics more generally – in order to emphasize urgency and impact, it is common to emphasize the severity of the condition that is being studied, often using language that is nowadays considered inadequate. For example, many publications use language that people “suffer from autism” or are “epileptic”. In 2023, we bristle at this language and often include more patient-focused language (“autistic” and “have epilepsy”), but there are many tendencies of which we are unaware. For example, many patient notes still use the language that individuals are “non-verbal” or “wheelchair-bound”.

Othering. The tone of this type of language is often referred to as “othering” – seeing individuals affected by disease as different from oneself. In addition, this often carries a value judgement. Going forward, I believe that two things are important. First, trying to avoid ableism as much as possible and create awareness when ableism is masked as scientific urgency. Second, creating awareness in the advocacy sphere that scientists are fallible, and that inadequate use of ableist language may not invalidate the underlying scientific idea. For example, when it comes to stuttering genetics, no matter how inadequate language may be that researchers include in their grants and publications, scientific knowledge builds over time, and the risk of using results for any discriminatory activities is extremely low given the overall frameworks used in genomic medicine and the fact that stuttering is likely highly polygenic.

Questions about the advocacy approach. In contrast to many other fields in neurogenetics, the stuttering field is underserved when it comes to research, but also diagnostic work-up. I would like to make the argument that every child with a persistent stutter deserves a full work-up, as is typically performed with all other neurodevelopmental conditions. It is state-of-the-art to discuss genetic testing for a child with autism or speech apraxia, but it still seems out of the ordinary for individuals who stutter. Movement disorders may masquerade as stuttering, and new-onset stuttering may be a clue towards an underlying progressive neurological condition such as a storage disorder. However, the number of individuals with stuttering seen by neurologists is very low, and the interdisciplinary field between speech therapy, neurology, and neurogenetics is virtually non-existing. This is somewhat unique for neurodevelopmental disorders. For example, individuals with Tourette Syndrome, a chronic disorder, are typically followed by a neurologist. Again, there is no single individual to blame for this, but I am surprised by the lack of momentum to systematically perform diagnostic testing in individuals who stutter.

Participatory research. In their commentary entitled “The disabling nature of hope in discovering a biological explanation of stuttering”, Prabhat and collaborators suggest participatory research with people who stutter as an antidote to ableism. I agree, but also see conceptual issues with this approach when looking at how genomic research typically works. There is no doubt that participatory research is a worthwhile endeavor, but as a genomic scientist, I need to ask whether I would rather perform an analysis of 2,000 individuals recruited through participatory research or 20,000 individuals through existing research studies. Again, I can hopefully say this so pointedly as I am talking about my own condition, where I am seeing myself as a research participant. Participatory research is useful in various areas in science, but may not be the best vehicle to generate large-scale genomic data.

Let some research be non-participatory. Large-scale genomic research often needs to be decidedly non-participatory, and research protocols are focused more on privacy protection and data safety rather providing data back to individuals. Does this mean that we should sanction this type of research that has generated major insight into many conditions that we treat clinically in neurogenetics? Some findings need to be discovered first in individuals before they can be shared with individuals. Again, this is by design to enable large cohorts of individuals quickly, for example through biobanks. What I would personally wish from stuttering advocacy is perspective – trying to take a broader point of view to see how progress has been made in other neurodevelopmental conditions, while keeping in mind how stuttering would truly benefit from similar approaches.