Dysfluency. I typically reserve my more contemplative blog posts for our summer beach vacation, but there are some thoughts that I had during this Spring Break that I wanted to share. In brief, I read Life on Delay by John Hendrickson and started reading The Beginning of Infinity by David Deutsch. At first glance, these two books couldn’t be any more different – a story about bullying, depression, isolation, and other issues that people who stutter face on a daily basis, and a wide-ranging narrative about the cosmic power of the search for good, scientific explanations. Then something occurred to me: there are two ways to spell dysfluency/disfluency. Hendrickson spells dysfluency with an “I,” while the scientific literature often prefers the “Y”. And this ambivalence may actually tell us something about the nature of neurogenetics more broadly.

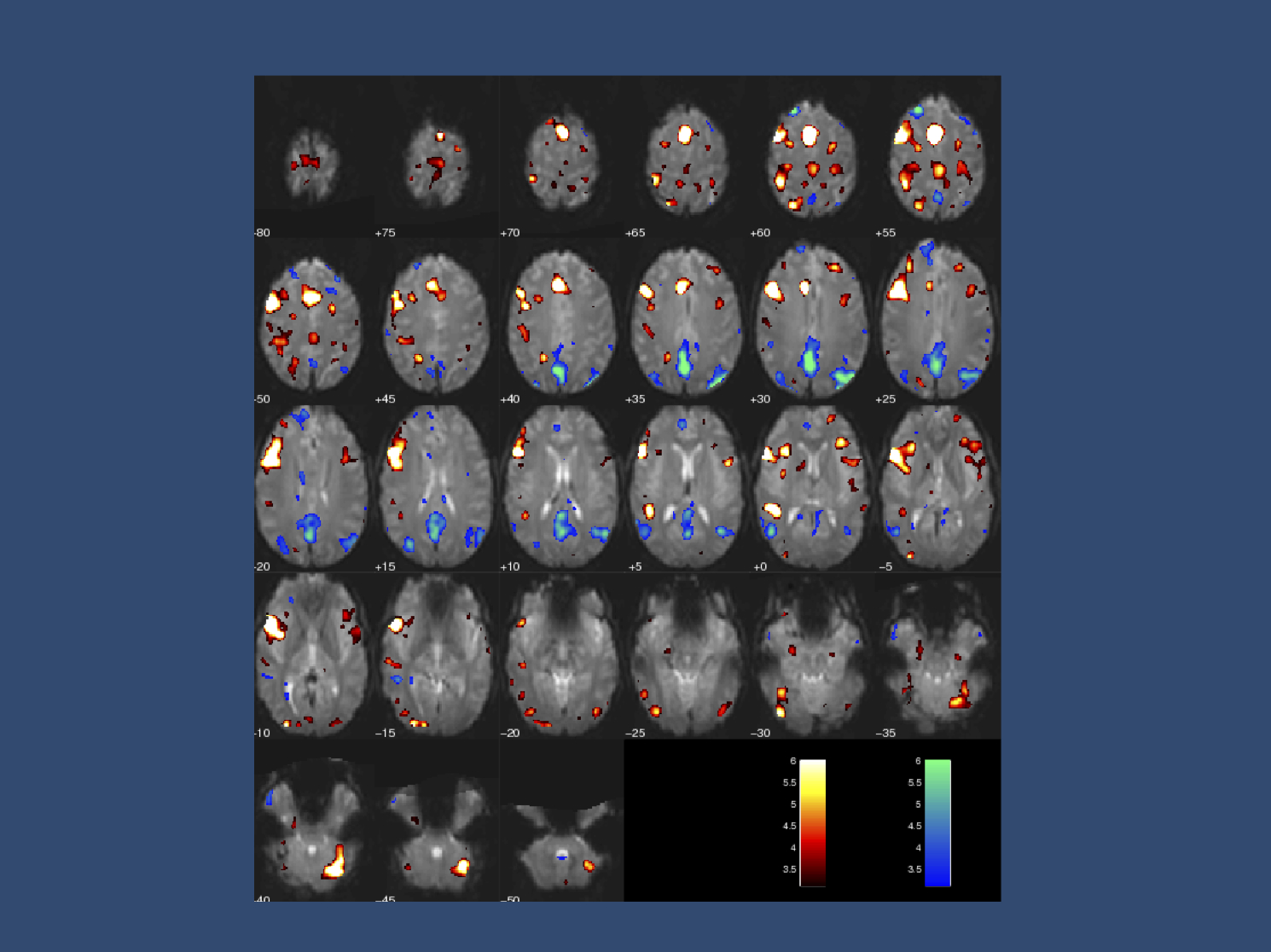

Figure 1. In early 2008, I managed to fail as a control in a functional MRI study performed in the Brain Research Centre in Melbourne, Australia. The colorful blobs indicate activation of brain regions during speech. It took me a minute to realize that my speech was actually on the wrong side, likely as a consequence of some alterations in my left hemisphere, as is regularly observed in people who stutter. I was supposed to be a control for an epilepsy study, but they probably took me out.

I&Y. Before I charge too far ahead, let me explain what I mean by the I and the Why. In brief, it is a way of conceptualizing the different approaches to what I would refer to as neurodiverse condition. The “I” is the subjective aspect, looking at the challenges that individuals face within society, but also the awareness that differences are not necessarily deficiencies, that there are sometimes unexpected benefits to disability, and there is often an aspect related to community-building, sharing experiences, and, hopefully, being at peace with one’s difference. This narrative is central to the disability rights movement, has been adopted by the autism/neurodiversity community, and is slowly emerging in the stuttering community. John Hendrickson, the author of Life on Delay, will be remembered for his insightful article on Joe Biden’s stutter.

Biden’s stutter. Yes, the current US president is a person who stutters and has basically convinced the entire world for the last three years that his stutter is a thing of the past, hiding his ongoing stutter in subtle pauses and occasional word substitutions. Please don’t get me wrong, I consider this an amazing feat that is unfortunately necessary given the way that the world looks at people who stutter. Hendrickson’s book is the author’s reflection on his own journey through the many hardships of a person who stutters in a world that often emphasizes fluency over communication, appearance over meaning. This is the “I” of stuttering, understanding where you find yourself in this world as a person who stutters.

Fluency rebels. Stuttering is about your words getting stuck in the most embarrassing situations in life. Reading about the stuttering journey sometimes feels like shame, insecurity and feelings of inferiority are a necessary part of stuttering. This is where the neurodiversity way of thinking comes in, unmasking the idea that people “suffer” from stuttering as ableism. Stuttering is not shameful per se, it only stands out in a world that prizes fluency. Hendrickson writes about New York artist Jerome Ellis (who pointedly calls himself JJJJJerome Ellis), who emphasizes the rebellious and creative side of being a person who stutters. There is something extremely disobedient about forcing people to wait and not talk without a pause. There is also something very powerful in knowing that 99% of the world population basically does not have an idea what fluency is, as they take it for granted.

Dysfluent waters. It’s like the fish that takes the water of the ocean for granted as it has always been there. People who stutter feel this water on a daily basis, as it is dysfluent. It is often a burden, but it is a sensitivity that the vast majority of the world population cannot have. This explains the heightened sensitivity of people who stutter to non-verbal communication, the proverbial “antennae” that people who stutter have when enter a room and almost automatically sense the mood. These considerations lead into discussions about the “stuttering benefit” – if prominent philosophers, scientists, and presidents are people who stutter, there is something that stuttering truly adds to this world. In other words, a non-stuttering world might actually be relatively boring. Temple Grandin, one of the pioneers of autism self-advocacy, is often cited with the following quote “What would happen if the autism gene was eliminated from the gene pool? You would have a bunch of people standing around in a cave, chatting and socializing and not getting anything done”. I guess you could make a similar case for stuttering, as well.

The Why. I hope I have built up a powerful story about accepting stuttering and potentially glimpsing at the inherent benefits by now. Stuttering is a condition that challenges our understanding of communication in ways that you would not expect, it provides an insight into the true reality of communication that is basically inaccessible for anyone who is not dysfluent. It truly is a difference, not a deficit. However, I would like to make this very passionate case that even the most powerful study about accepting stuttering as diversity and re-shaping our experience as people who stutter is very incomplete. It is about personal experiences, calling out societal expectations for what they are, and for seeing it as a difference and not as a deficit. What do I feel is missing in here? How can a powerful story about self-empowerment and diversity be incomplete? Here is my answer: it is incomplete as is misses the “why” – Y-dysfluency rather than I-disfluency.

Infinity. David Deutsch’s book is a powerful statement about the role of scientific thought. The underlying theme of The Beginning of Infinity suggests that once humans discovered the scientific method, things took off and they are unlikely to stop. Once we replace superstition, authority, and unquestioned beliefs by the search for good, scientific explanations, we are able to understand things ranging from subatomic particles to entire galaxies. Ongoing progress in understanding the most complex structure in the known universe, the human brain, goes along with it. Unfortunately, asking “why” with regards to stuttering is sometimes seen as a threat to self-advocacy. Stuttering is genetic, and the idea of finding a “stuttering gene” is sometimes seen as a first step towards discrimination. Having slowly tapped into stuttering genetics in the last two years, I was surprised how often I was confronted with this sentiment. Unfortunately, the “I”-perspective (advocacy) is often seen as a conflict to the “why”-perspective (scientific analysis), which to me is a slippery slope. Scientific understanding can be extremely empowering and adds to the advocacy perspective rather than diminishing it.

What neurogenetics can learn from stuttering research. So far, I have not yet mentioned the figure that I have attached to this blog post. Again, as with prior blog post, this is my brain on stuttering. Bilateral activation of the speech areas on a functional MRI obtained for a completely different purpose, showing the developmental differences that some people who stutter have. Stuttering happens in the brain and has a scientific explanation. It is not just a lived experience that is improved by advocacy, but a neurological difference. And the more we understand this difference scientifically, the more we’re approaching infinity. This is blog post 1/2. In the next post, I want to look at on how the absence of genomic studies in stuttering actually tells us something about neurogenetics more generally.