Telehealth. Yes, looking at my last post, this blog has been silent for a while. With the COVID-19 pandemic ongoing, it has been difficult to find a good launching point to write about genetic epilepsies again without somehow feeling that I’m missing the point with regards to the major challenges that the epilepsy genetic community is facing in 2020. But was has actually happened in epilepsy genetics in the United States during the pandemic? In parallel to the dramatic medical issues at the frontline, something very interesting has happened in the background – the shift from in-person medicine to telemedicine, including the vast majority of outpatient visits in child neurology. Telemedicine, remote healthcare services that include audio and video equipment, has long been technically feasible, but has led a niche existence due to licensing restrictions and lack of reimbursement. However, this all changed quickly during the COVID-19 pandemic. But did this transition work? Is telemedicine really as effective as suggested and were we able to provide care along the entire spectrum of disorders in child neurology, including the genetic epilepsies? In a new publication in Neurology, we analyzed more than 2,500 telehealth visits in child neurology, facilitated by a new healthcare analytics pipeline that we built in response to the challenges of the telemedicine transition.

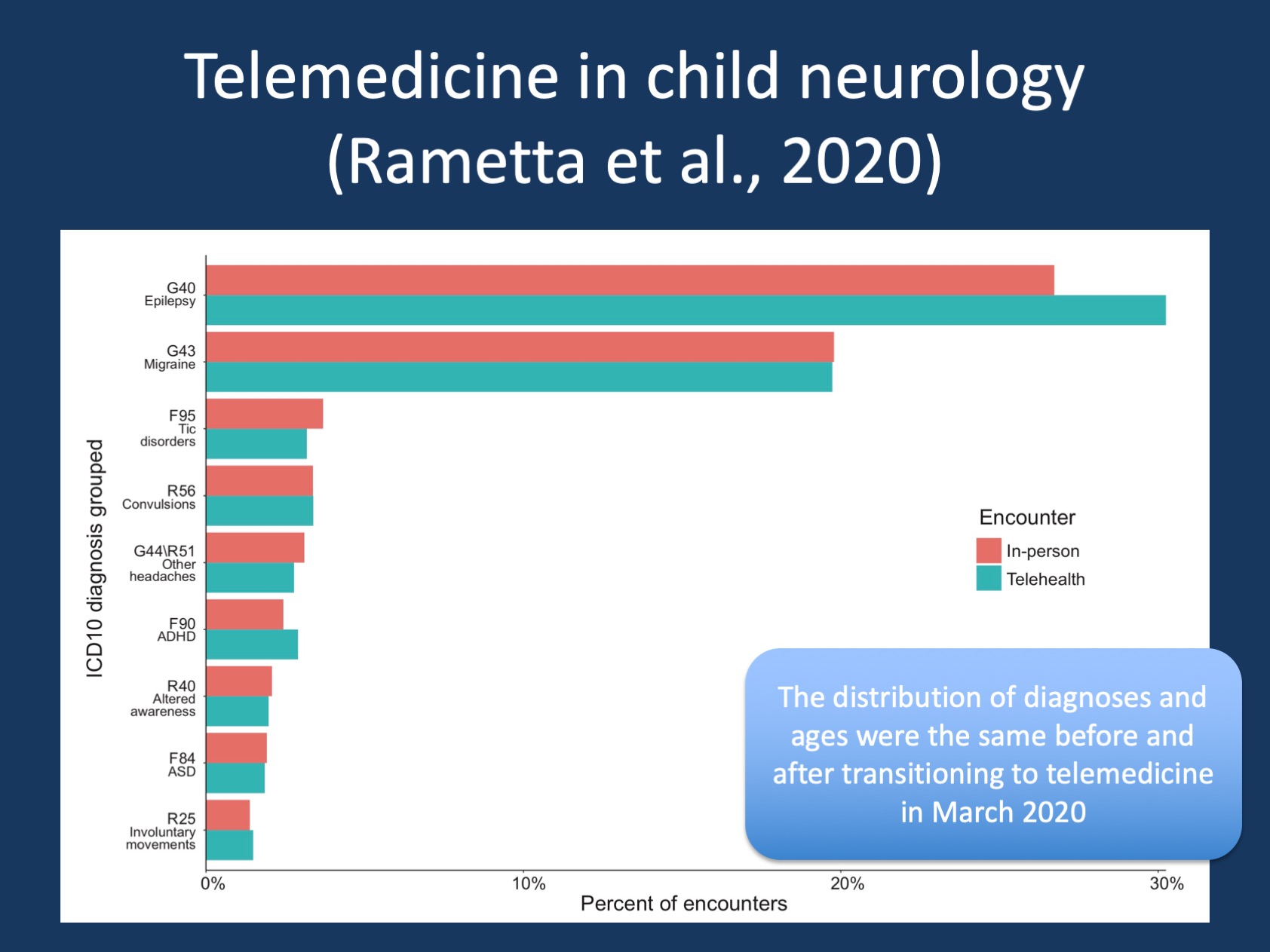

Figure 1. Analyzing 2,589 Child Neurology Telehealth Encounters Necessitated by the COVID-19 Pandemic. We used a novel health care analytics framework to assess patient demographics, age distribution, and diagnoses in 14,780 in- person encounters and 2,589 telehealth encounters. We found that telemedicine in child neurology is feasible and effective, covering the full age and diagnostic range typically seen in an outpatient child neurology clinic.

Electronic medical records. Let me quickly explain what a blog post on telemedicine is doing on our epilepsy genetics blog. Over the last two years, our team has been expanding our research efforts into understanding so-called “computational phenotypes”, representations of clinical courses in children with genetic epilepsies that we can subject to large-scale analyses given that most of the disorders we see are very rare where it is often challenging to make predictions about outcomes and longitudinal disease course. One of the resources that our team has become quite familiar with are the electronic medical records (EMR). In the US, more than 85% of all medical centers use electronic medical records, and this data can be mined and systematically analyzed. And I should note that this analysis is often not straightforward, requires data harmonization and has many peculiarities that I’ll address at another time on this blog – this is short for “don’t get me started” as I could easily fill a post writing about this. The scale at which data is available in the EMR more than compensates for the complexities of this data resource.

Health care analytics. The EMR also happens to be the place where much of the data on telemedicine visits are deposited, which is why we got involved in this in the first place. In a joint effort with my clinical and informatics colleagues, we built a new framework to assess our telemedicine visits, basically inventing a new field of science that I would like to refer to as child neurology telemedicine healthcare analytics. We examined distributions of diagnoses and patient demographics and used Natural Language Processing to mine a provider questionnaire assessing the feasibility of telemedicine in this patient population. But what did we find?

Child neurology telemedicine. First of all, telemedicine is feasible for a large patient volume. After an initial dip in weekly outpatient visits as we rapidly adjusted to a new model of healthcare delivery, the number of patient visits quickly rebounded. We used a combination of two telehealth options: audio-video telemedicine and structured telephone encounters for families where telemedicine was not possible. For our analysis, we captured approximately 2,000 telemedicine and 500 telephone visits and compared them to a little more than 14,000 prior in-person visits. We found that the distribution of patient diagnoses and ages was the same before and after the transition to telemedicine with a small excess of epilepsy visits through telemedicine. This basically means that we were able to cover the entire spectrum of diagnoses in child neurology through telemedicine, something that was not known previously and strongly supports the notion that telemedicine can be considered an important piece of the child neurology toolbox in the future.

Questionnaire analysis. A main piece of our study was the analysis of provider questionnaires that we embedded in patient notes and that were filled out for approximately 60% of all patient visits. We asked about satisfaction with telemedicine, plans for future use, technical challenges, and most importantly, whether the clinical features of our patients were concerning enough that the patient required immediate in-person follow-up, the so-called “Visits of Concern” (VOCs). In brief, providers were satisfied with the visit in 90%, and, if available, would chose telemedicine in at last 80% of follow-up visits. Roughly 40% of visits were plagued by technical challenges, which indicates that our ability to provide care through telemedicine far outpaces the technical possibilities. The “Visits of Concern” accounted for approximately 5% of all visits, which was stable throughout the observation period of our study. This means that in outpatient child neurology on average every twentieth patient needs to be seen in person and required more immediate action, such as admission to an emergency room. For all our VOCs, we found that adequate steps were taken by the providers, suggesting that the framework under which telemedicine was delivered also provided a “safety valve” for patient interactions that required immediate in-person medical attention.

The digital divide. Telemedicine cannot be provided to everybody, and there is the justified concern that individuals in underserved communities may be left behind with this novel technology. We found that individuals from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds were more likely to have telephone encounters compared to audio-visual telemedicine visits, as did individuals who lived in areas with a lower median household income. While the ratio of individuals in racial and ethnic minority groups seen did not differ before and after transition to telemedicine, the relative difference between families who we could connect with through audio-visual telemedicine and those who connected via telephone remains concerning. What we could document is that while telemedicine is promising for child neurology at large, there is a critical need to develop strategies to bridge the digital divide and make this mode of healthcare delivery feasible for individuals from underserved communities, where healthcare disparities are already known to exist.

What you need to know. Telemedicine in child neurology works. It is feasible and effective, and, if strategies are in place, safe for the estimated 5% of patients who present with concerning clinical features requiring prompt in-person follow-up. While there is ongoing discussion if and how telemedicine can be continued in the future, our study adds an important puzzle piece in understanding the quality and value of remote child neurology care.