HSP. I have to admit that the hereditary spastic paraplegias are not mentioned all that frequently on our blog. The main reason is that there is little overlap between early-onset epilepsies and adult-onset progressive neurodegenerative conditions that are characterized by spasticity and weakness in the lower extremities. In a recent publication, we described an epilepsy gene that became an HSP gene, showing an unusual overlap between both groups of conditions and establishing a novel mechanism in HSP pathogenesis. Here is a continuation of the KCNA2 story.

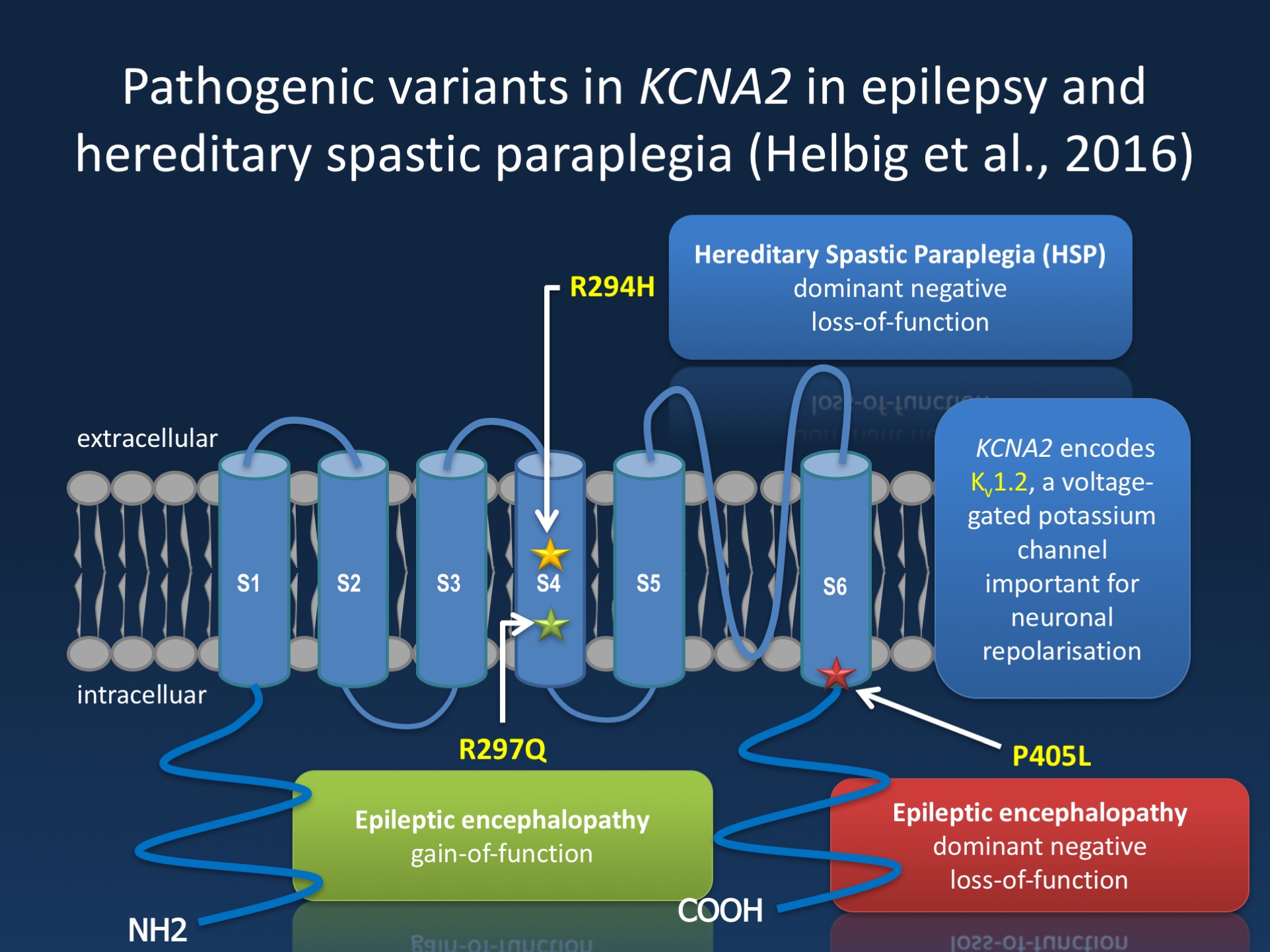

Figure. The Kv1.2 channel (encoded by KCNA2) is a brain-expressed potassium channel, which has six transmembrane domains. KCNA2 encephalopathy falls into two big groups, the “A phenotype” due to activating mutations in the voltage sensor and “B phenotype” due to dominant-negative loss of function mutations outside of the voltage sensor . In the recent publication by Helbig and collaborators, we identify a novel recurrent KCNA2 pathogenic variant in the voltage sensor (R294H) leading to loss-of-function in patients with spastic paraplegia.

Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia. Broadly speaking, a neurology division encounters genetics on two different levels. On the pediatric side, genetics is driven by neurodevelopmental disorders (including autism, intellectual disability, and epilepsy) and genetics of rare recessive disorders. On the pediatric side, the epilepsies have set the pace of gene discovery in the last few years. On the adult side, many patients with genetic conditions are seen by movement specialists, as patients have inherited neuropathies or spastic paraplegias, or by cognitive neurologists due to familial dementia syndromes. Hence, there is little overlap between pediatric neurogenetics and adult neurogenetics. The hereditary spastic paraplegias are a group of neurodegenerative conditions characterized by spasticity and weakness in the lower extremities due to a progressive degeneration of the long corticospinal fibers that reach from the motor cortex to the spinal cord. Genetically, the hereditary spastic paraplegias are highly heterogeneous.

The HSP genes. The onset of HSP may occur at any time during life, but most cases manifest in adulthood. Accordingly, child neurologists rarely encounter these conditions and are therefore perplexed by the heterogeneity of the HSPs. To date, 72 types of HSP have been described and more than 50 types of HSP have been genetically characterized, easily matching the complexity of epilepsy genes. The different spastic paraplegias carry the designation SPG. The most common HSP is SPG4 due to mutations in the spastin gene.

KCNA2. We initially described pathogenic variants in KCNA2 in patients with epileptic encephalopathies. The mutational spectrum of KCNA2 includes two recurrent pathogenic variants that we initially referred to the “A” (R297Q) with gain-of-function and the “B” variant (P405L) with a loss-of-function of the Kv1.2 channel. We are currently in the process of better understanding the phenotypes of these and other variants. In our recent study, we describe three families with a novel pathogenic variant (R294H), located in the same voltage sensing region as the R297Q variant. Interestingly, patients carrying the R294H variant do not present with the early-onset epileptic encephalopathies that we initially described. In contrast, the phenotype of these families is characterized by HSP. This is surprising as none of the other 72 genes for HSP are ion channel genes. In functional studies, we demonstrated that this variant located in the voltage sensor leads to a dominant-negative effect on KCNA2 function.

Phenotypes. My wife and partner in crime Katie is first author on the current publication in Annals of Neurology. Katie identified the first family with KCNA2-related HSP through a diagnostic exome study in her role as an exome analyst at Ambry Genetics. The phenotypes of the families described in our recent publication add a new twist to the KCNA2 story. Families 1 and 2 have dominantly inherited complicated HSP. A hereditary spastic paraplegia is considered complicated if there are additional clinical features. In the case of both KCNA2 families, these additional features consisted of cognitive impairment, ataxia, and sensory-motor axonal demyelinating peripheral neuropathy in some patients. Family 3 is even a more complex example of how genes for neurological conditions run in families. The affected individuals in this family were two sisters with early-onset absence epilepsy and intellectual disability, but only one sister carried the R294H variant, which was de novo. The sister carrying the R294H variant had an ataxic gait and hand tremor at 3 years, which was not present in her sister. In addition, the sister carrying the R294H variant had several prolonged febrile seizures; her sister only had a single febrile seizure. Spasticity was not noted at age 20 in the sister carrying the pathogenic variant.

From EE to HSP. While putting together this blog post, I learned that our publication of KCNA2 in HSP received the ultimate accolade for a gene discovery in neuromuscular disorders – a mention on the neuromuscular homepage. This webpage, the ultimate online resource for everything neuromuscular, had been our template for the Channelopathist ever since the initial start of our blog. Yes, our style is different, but the neuromuscular homepage has always been something to look up to for us. This strange cross-over project was made possible as KCNA2 became a gene for HSP, an unusual twist for a rare gene for epileptic encephalopathies. Other, more common genes for human epilepsies are definitely not involved in HSP, suggesting that the mechanism linking both conditions is not due to a non-specific presentation of neurodevelopmental conditions, but specific to KCNA2. We will need to have further studies to better understand the molecular basis of these dual phenotypes and what the specific mutations are doing to predispose their carriers to either epilepsy or HSP.

This is what you need to know. The KCNA2 gene was previously identified in patients with epileptic encephalopathies. In a current publication in the Annals of Neurology, we identify a recurrent KCNA2 variant as a novel cause of hereditary spastic paraplegia, suggesting an unexpected overlap between the epilepsies and neurodegenerative disorders.