Completing the SCN8A spectrum. SCN1A was initially discovered in GEFS+, an autosomal dominant familial epilepsy syndrome. SCN2A was first identified in Benign Familial Neonatal-Infantile Seizures (BFNIS), also representing an autosomal dominant familial epilepsy syndrome. SCN8A, the third epilepsy-related sodium channel gene, has only been associated with severe, sporadic cases so far, not with more benign familial epilepsies. In a recent publication in Annals of Neurology, a novel recurrent mutation in SCN8A is identified, which causes benign infantile seizures and paroxysmal dyskinesia. While this finding adds the missing familial epilepsy syndrome to SCN8A, it also provides an intriguing link to the phenotypes caused by PRRT2.

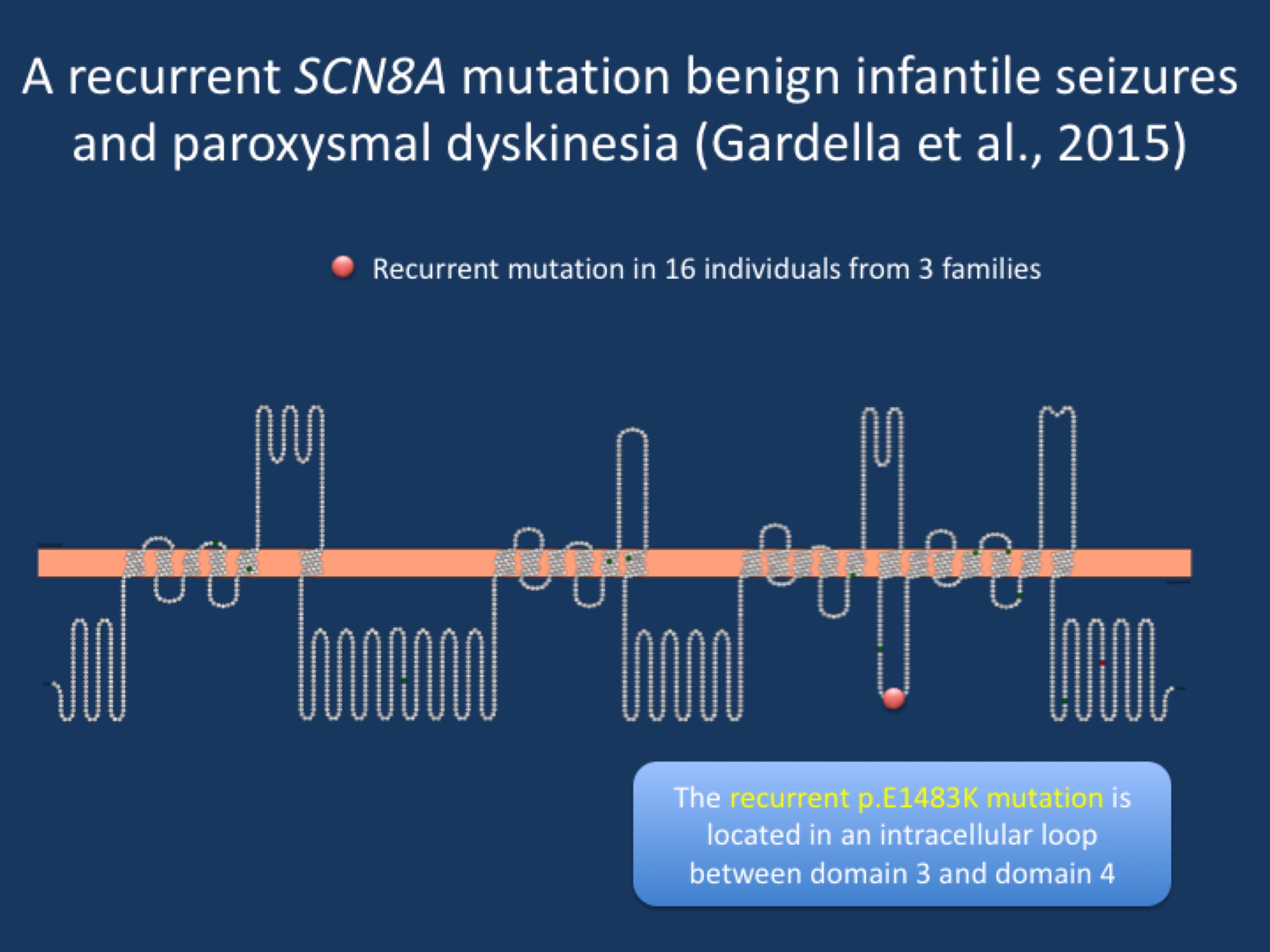

Figure. Cartoon of the SCN8A protein, demonstrating the location of the recurrent p.E1483K mutation. The mutation is located in an intracellular loop, suggesting a specific function of this region that appears to be tightly linked to an uncommon SCN8A phenotype.

Benign Familial Infantile Seizures. Gene identification in benign familial infantile seizures has been a long and complicated story. While familial forms of neonatal seizures were one of the first genetic epilepsies to be identified, the discovery of the culprit gene for familial infantile seizures took several decades. Finally, in 2011, the PRRT2 gene was identified as the major gene for familial infantile seizures. However, there were still families that were PRRT2 negative. In addition, a complex overlap of infantile seizures and dyskinesias had long been observed. In their recent publication, Gardella and collaborators identify a recurrent p.E1483K mutation as the cause of this combined syndrome in 3 families with a total of 16 affected family members.

Dyskinesias. Episodic movement disorders are known to occur in conjunction with familial infantile seizures. When families demonstrate infantile seizures and paroxysmal kinesogenic dyskinesias, this combination is sometimes referred to as infantile convulsions and paroxysmal choreoathetosis (ICCA). Dyskinesias are intermittent movement disorders that can present as dystonia, chorea, and ballism and can vary in duration. Typically, three different types of paroxysmal dyskinesias are distinguished including paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia (PKD), paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia (PNKD), and paroxysmal exercise-induced dyskinesia (PED). The description kinesogenic refers to the fact that attacks can be brought on by sudden movements. The gene encoding paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia protein (PNKD) is also called myofibrillogenesis regulator 1 and is the only known gene for this condition. The gene for PED is GLUT1 (SLC2A1). For PKD, the PRRT2 gene has been the only known candidate so far.

SCN8A discovery. In the study by Gardella and collaborators, three families with BFIS/ICCA were found to have an identical SCN8A mutation. All three families were not related, as was shown by the analysis of the haplotypes. In contrast to other SCN8A mutations that affect the pore region of the ion channel, the recurrent p.E1483K mutation is located in an intracellular loop. Loop regions are typically thought of as passive linkers between the transmembrane segment and, comparing across species, are poorly conserved. However, the particular region affected by the recurrent p.E1483K mutation appears to be highly conserved, suggesting that this particular intracellular loop either affects ion channel function or is important for binding to other proteins. The authors do not present functional studies in the current publication, but provide a broad overview of the clinical phenotypes in their patients. It will be interesting to know how this mutation affects the overall function of the SCN8A protein.

This is what you need to know. Prior to the discovery of PRRT2, benign familial infantile seizures were thought to be due to ion channel disorders, paralleling the observation on SCN1A and SCN2A. Finally, in 2015, we have found the ion channel gene that explains at least a small proportion of cases, while the majority of families carry PRRT2 mutations. The BFIS/ICCA families have a recurrent SCN8A mutation, suggesting that this phenotype is very closely linked to the function of this mutation, which codes for and amino acid that is located in an intracellular loop. Future studies will assess how this particular mutation is so specific for an uncommon SCN8A phenotype.