Suppression-burst. Ohtahara Syndrome is a rare epileptic encephalopathy with onset in the first weeks of life. The typical EEG feature of Ohtahara Syndrome is suppression-burst activity, suggesting a profound disruption of cerebral function. Ohtahara Syndrome can be caused by severe brain malformations and neurometabolic disorders. In addition, mutations in ARX and STXBP1 are known causes of Ohtahara Syndrome. In a recent publication in Epilepsia, genetic alterations in CASK were identified in patients with Ohtahara Syndrome and cerebellar hypoplasia. Given that CASK mutations are the known cause for a complex X-chromosomal disorder, this report provides us with an interesting example of what happens when genes underlying distinct clinical dysmorphology syndromes cross over to the epilepsies.

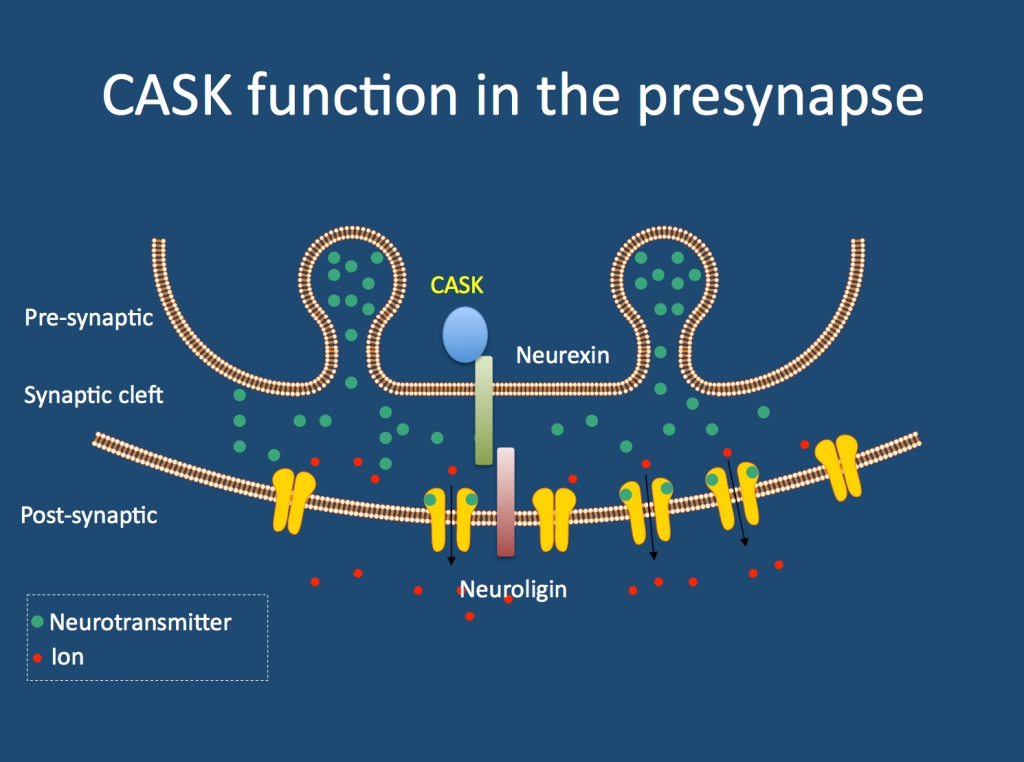

CASK. Let’s introduce the gene first. CASK stands for calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine protein kinase. The CASK protein has been found to be part of the presynaptic structure, where it binds and interacts with neurexins. This particular interaction is interesting from the viewpoint of neurodevelopmental disorders, as alterations in neurexins, neuroligins and other presynaptic structural proteins are implicated in autism, intellectual disability, schizophrenia and epilepsy. Other functions of CASK beyond the presynapse have also been described. So what happens if CASK is disrupted?

Known CASK phenotypes. Mutations in CASK are known to cause a spectrum of disorders including non-syndromic intellectual disability in females, microcephaly and pontocerebellar hypoplasia and FG syndrome, characterized by multiple congenital abnormalities, intellectual disability and a prominent congenital nystagmus. As CASK is an X-chromosomal gene, it is assumed that the milder phenotypes in females are compensated for by the remaining copy of the CASK gene. In the reported male patients, there is some evidence for partial exon skipping, which may generate functional proteins through leaving some of the exons out. Either way, CASK phenotypes are a broad range of intellectual disability syndromes with or without congenital abnormalities and pontocerebellar hypoplasia. None of the previous reports, however, has indicated that epilepsy is the predominant phenotype in individuals with CASK alterations.

CASK and epilepsy. Saitu and colleagues performed array CGH in 34 patients and exon sequencing in 12 patients with Ohtahara Syndrome. They identified two male patients with alterations in CASK; one patient with a partial deletion of CASK and one patient with a de novo mutation in this gene. The deletion was inherited from an unaffected mother with probable mosaicism, i.e. the deletion was only present in a certain percentage of the mother’s cells. The authors demonstrate that both alterations result in a complete loss of CASK protein in lymphoblasts, as the single copy on the X-chromosome in the male patients is altered. This complete loss of CASK protein is considered to be causal by the authors in contrast to the milder phenotypes in affected females. The authors also note that both patients have cerebellar hypoplasia and some minor dysmorphic features.

Epileptic encephalopathies in the context of dysmorphic features. Even though seizures are frequently seen in patients with genetic dysmorphology syndromes, severe early-onset epilepsies leading to the severe presentation of suppression-burst activity are an exception. Except for ARX and STXBP1, no other genes for Ohtahara Syndrome are known. Therefore, the finding by Saitsu and colleagues is interesting as it highlights a novel candidate gene for this severe disorder. While cerebellar hypoplasia is a distinct finding on MRI, it is sometimes attributed to the effect of antiepileptic drugs or secondary to the epilepsy. Therefore, recognition of CASK phenotypes might receive some attention in patients with severe epileptic encephalopathies.